Military Amebiasis Prevention Checklist

This interactive checklist helps military personnel ensure proper infection control measures are in place to prevent amebiasis outbreaks during deployments.

Quick Takeaways

- Amebiasis spreads through contaminated water and food, a common issue in field environments.

- Military deployments face unique sanitation hurdles that civilian settings rarely encounter.

- Effective control relies on portable water purification, rapid diagnostics, and strict hygiene training.

- Standard anti‑amoebic drugs work, but logistics and medication stability are critical on the move.

- Commanders benefit from a concise checklist to keep troops safe during missions.

Amebiasis is a parasitic infection caused by Entamoeba histolytica. The parasite lives in cyst form outside the body and becomes active once ingested, attacking the intestine and, in severe cases, the liver. Symptoms range from mild diarrhea to life‑threatening dysentery and abscesses. In civilian hospitals the disease is treatable, but on the battlefield the same infection can cripple a unit’s operational readiness.

Why does the military bother with a disease that most civilians only see in travel clinics? The answer lies in the environment. Remote training grounds, desert bases, jungle patrols, and humanitarian missions often rely on untreated surface water, shared latrines, and field kitchens that lack proper waste disposal. Add close‑quarter living and limited medical supplies, and you have a perfect storm for amebiasis to spread.

Understanding the Enemy: Amebiasis Basics

The life cycle of Entamoeba histolytica has two stages: the infective cyst and the invasive trophozoite. Cysts survive weeks in water, making them hard to eradicate without proper filtration or chlorination. Once inside a host, trophozoites attach to the colon lining, release enzymes, and cause tissue damage. Rapid diagnosis is essential; stool microscopy, antigen detection kits, and PCR are the main tools, but they require labs that aren’t always mobile.

Military‑Specific Infection‑Control Challenges

1. Field sanitation is often improvised. Portable latrines, if not dug far enough from water sources, become a breeding ground for cysts. 2. Water purification units can fail under extreme temperatures, leaving troops to drink from rivers that may be contaminated. 3. Medical staff operate in deployable medical units with limited lab capacity, making point‑of‑care testing a premium. 4. The fast‑moving nature of operations means medication stockpiles can expire or be lost, jeopardizing treatment continuity.

Comparing Civilian and Military Infection‑Control Approaches

| Aspect | Civilian Settings | Military Field Settings |

|---|---|---|

| Water Source | Municipal supply with routine testing | Surface water, emergency filtration, variable testing |

| Sanitation Facilities | Permanent sewers, regulated waste | Portable latrines, often within 50m of water |

| Diagnostic Capacity | Full labs, culture, PCR | Rapid antigen kits, limited PCR |

| Treatment Logistics | Pharmacy stocks, stable supply chains | Field kits, temperature‑sensitive meds, resupply delays |

| Training Emphasis | Public‑health campaigns, occasional drills | Pre‑deployment briefings, daily hygiene checks |

Proactive Measures: Military‑Tailored Prevention

Pre‑deployment health packs now include a water purification tablet regimen that neutralizes cysts in under 30minutes. Troops receive a two‑hour classroom session on the dangers of drinking untreated water, followed by a field drill where each soldier must demonstrate proper latrine placement using a simple distance‑to‑water calculator.

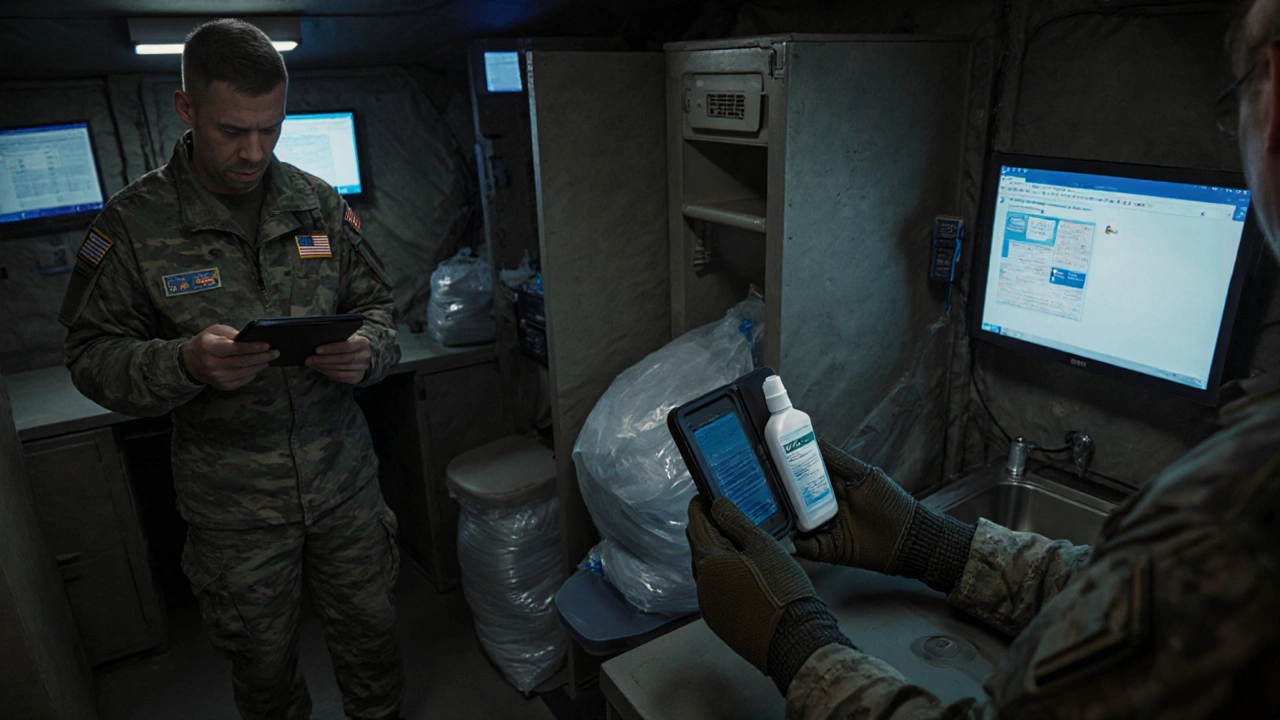

Medical units carry handheld antigen detection kits that deliver results in 15minutes, enabling immediate isolation of suspected cases. For longer missions, a metronidazole stock is pre‑packaged in heat‑stable blister packs to survive desert heat. Commanders also enforce a “no‑share” rule for personal water bottles, cutting down cross‑contamination.

Treatment on the Frontline

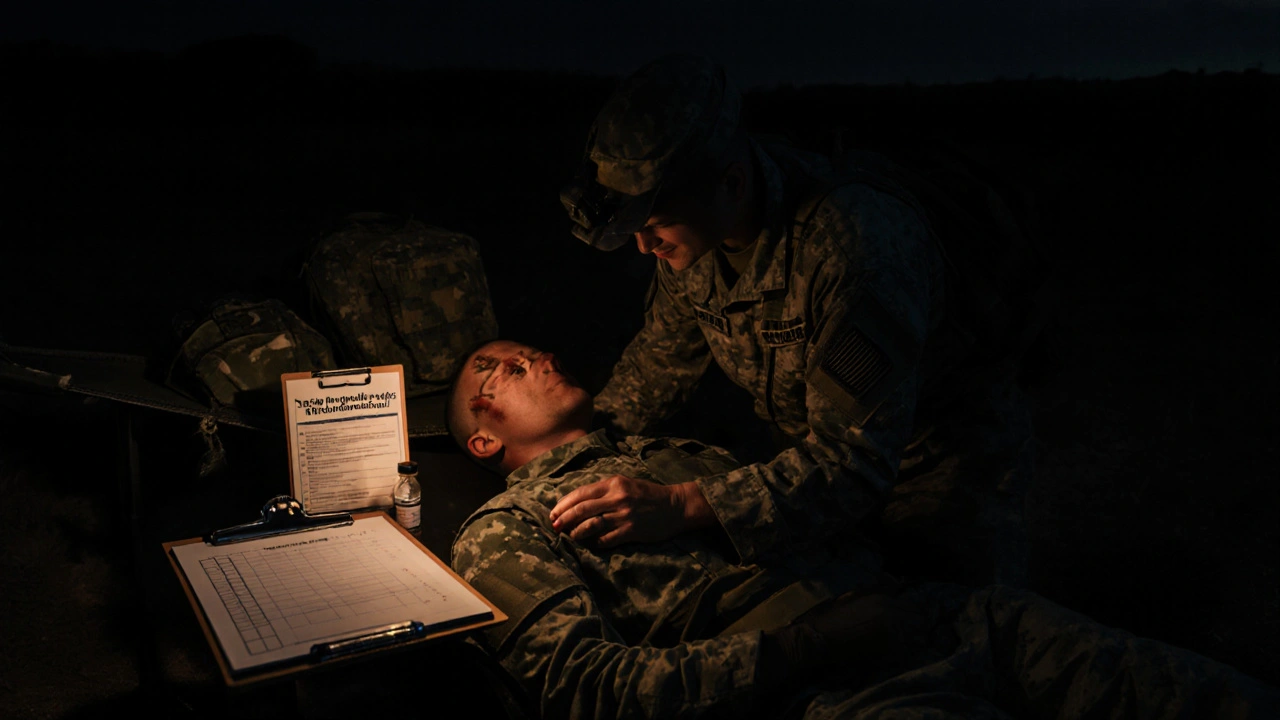

When a soldier shows classic dysentery, the protocol is simple: start a 5‑day course of metronidazole (or tinidazole where available) and add a luminal agent like paromomycin to eradicate cysts in the gut. The biggest hurdle is ensuring the drug stays within its potency window-most field kits now include a temperature‑indicating label that flips from green to red if storage exceeds 30°C for 48hours.

If a liver abscess is suspected, the medic must request a forward surgical evacuation. In the meantime, an aggressive IV regimen of metronidazole is started to buy time. Logistics officers keep a “critical meds” manifest that flags anti‑amoebic drugs, ensuring they’re top of the resupply list.

Lessons from Past Outbreaks

During the early 2000s peacekeeping missions in the Balkans, several units reported clusters of amebiasis linked to a malfunctioning water purification unit. The response was swift: engineers replaced the unit, and the medical team introduced point‑of‑use chlorine tablets. The incident highlighted two key takeaways-always have a backup water treatment method and train all troops in basic chlorination.

World WarII field hospitals in the Pacific faced similar issues with tropical streams. The solution then was the widespread use of boiled water and portable charcoal filters. Modern technology has improved on that, but the principle remains: simple, low‑tech redundancy saves lives.

Command Checklist: Keeping Troops Safe from Amebiasis

- Verify all water sources are treated with approved filtration or chlorination.

- Inspect latrine placement-maintain at least 100m from water collection points.

- Conduct daily hygiene briefings; emphasize hand‑washing after restroom use.

- Ensure rapid‑test kits are stocked and staff are trained to use them.

- Maintain a temperature‑controlled cache of metronidazole and luminal agents.

- Log any gastrointestinal complaints immediately; isolate suspected cases.

- Run a monthly audit of water‑treatment equipment and medication expiration dates.

What If… Scenarios

Scenario A: The purification unit fails during a desert patrol. The immediate fix is to switch to chlorine tablets while engineers repair the unit. Troops should also boil water if fuel permits.

Scenario B: A sudden surge of diarrheal illness appears. Deploy the antigen detection kits, quarantine affected soldiers, and start empiric metronidazole while awaiting test confirmation.

Scenario C: Resupply is delayed, and medication stock is running low. Use the heat‑stable blister packs first, prioritize treatment for severe cases, and request emergency air‑drop of additional doses.

Frequently Asked Questions

How is amebiasis transmitted in a military setting?

The parasite spreads when soldiers ingest cysts from untreated water, contaminated food, or by hand‑to‑mouth contact after using inadequate latrines. Shared water sources and close‑quarter living amplify the risk.

What rapid diagnostic tools are practical on the field?

Handheld antigen detection kits that use stool samples and give results in 15 minutes are the most feasible. PCR is accurate but usually requires a mobile lab, so it’s reserved for larger forward operating bases.

Which medication is preferred for treating amebiasis in the field?

Metronidazole is the first‑line drug because it’s effective, inexpensive, and available in heat‑stable formulations. Tinidazole is an alternative if a single‑dose regimen is needed. A luminal agent like paromomycin should follow to clear cysts.

How can commanders ensure water safety without sophisticated equipment?

Carry chlorine tablets or iodine drops as a backup, and train troops to boil water when fuel is available. Portable ultrafiltration units with a 0.1µm membrane can also remove cysts effectively.

What are the signs that a liver abscess may have developed?

Persistent right‑upper‑quadrant pain, fever, and a tender liver on examination suggest an abscess. Ultrasound or CT imaging is required, so suspect cases are evacuated to a facility with imaging capability.

Zac James

September 29, 2025 AT 16:23Good reminder to keep water clean in the field.

Arthur Verdier

October 6, 2025 AT 03:56Wow, because apparently the military has never dealt with dirty water before, right? Let me guess, the next step is to hand out glittery water bottles and call it a day. We all know that a simple checklist is the pinnacle of scientific advancement. But sure, why not trust a PDF when a field medic could just eyeball the water. Imagine the horror of a soldier actually reading the manual before drinking. The real conspiracy is that governments hide the fact that chlorine tablets are a mind‑control agent. They probably laced them with microchips to track every bowel movement. And those rapid‑test kits? Just glorified fortune cookies that tell you if you’re lucky. If you think metronidazole can survive desert heat, you’re either a chemist or a magician. Stockpiling meds in heat‑stable blister packs is just a fancy way of saying 'we hope they don’t melt'. Honestly, the biggest threat isn’t the parasite but the paperwork that comes with every protocol. One more thing: the 'no‑share' water bottle rule is just an excuse to sell more plastic. I bet the real cost is hidden in the propaganda budget. All this talk about sanitation sounds like a plot to keep the troops occupied while the real war happens elsewhere. So, congratulations on the checklist, you’ve officially cured amebiasis with bureaucracy. Now if you’ll excuse me, I’m off to find the secret underground lab where they brew the chlorine tablets.

Breanna Mitchell

October 12, 2025 AT 15:29Great job highlighting how simple measures can save lives on the ground. The checklist format makes it easy for anyone to follow, even under stress. Keeping water safe is as crucial as any weapon you carry. Kudos to the team putting this together.

Alice Witland

October 19, 2025 AT 03:03Ah yes, because a table comparing civilian and military sanitation solves all the gritty field realities. Still, I appreciate the effort to lay out the differences in a tidy spreadsheet. It reminds us how much easier things are when you have permanent plumbing. Hopefully the troops get the same neatness in the desert.

Aly Neumeister

October 25, 2025 AT 14:36So, you’ve got a list, right, check every box, and hope for the best, no?

Olivia Crowe

November 1, 2025 AT 01:09When the water’s safe, the mission thrives – a simple truth.

Quinn S.

November 7, 2025 AT 12:43While the intent of the checklist is commendable, its execution suffers from a lack of precise terminology and inconsistent formatting, which may lead to misinterpretation among personnel. The document would benefit from a thorough edit to eliminate ambiguity and enforce standard operating procedures unequivocally.

Dilip Parmanand

November 14, 2025 AT 00:16Stay sharp, keep those filters humming, and never skip the chlorine step – you’ve got this!

Sarah Seddon

November 20, 2025 AT 11:49Imagine the relief of a soldier finally drinking clean water after a grueling march; it’s like finding an oasis in the middle of a scorching desert. Your checklist turns that fantasy into reality, and that’s something to celebrate!

Ari Kusumo Wibowo

November 26, 2025 AT 23:23Look, if you don’t want a whole unit down with dysentery, just follow the damn checklist. No excuses, no shortcuts.

Hannah Gorman

December 3, 2025 AT 10:56The perpetual tug‑of‑war between logistical constraints and medical necessities creates a perfect storm for opportunistic pathogens.

In my experience, the most effective strategy is not merely a list, but an ingrained cultural mindset that values hygiene above all.

When commanders internalize this philosophy, they allocate resources proactively rather than reactively.

Moreover, the integration of rapid diagnostics into the daily routine transforms suspicion into actionable data.

This shift from anecdotal reporting to evidence‑based isolation dramatically reduces transmission chains.

However, the true bottleneck often lies in training, where soldiers are taught to read manuals under fire.

If the training environment fails to simulate realistic stressors, the knowledge evaporates on the battlefield.

Therefore, continuous reinforcement through drills and after‑action reviews is indispensable.

Only by marrying technology, logistics, and human behavior can we hope to keep amebiasis at bay.

neethu Sreenivas

December 9, 2025 AT 22:29It’s clear how overwhelming water safety can feel in the field, and the checklist offers a gentle hand to guide you through. 🌿 Remember, every small step you take protects not just yourself but the whole team.

Keli Richards

December 16, 2025 AT 10:03Just another day remembering to filter water and wash hands it makes sense keep the troops healthy

Ravikumar Padala

December 22, 2025 AT 21:36I suppose the checklist isn’t bad, but it feels like it was cobbled together during a coffee break. It lists the obvious things, like “treat water,” which any decent commander already knows. The real issue is the lack of detail on how to handle equipment failure in extreme heat. Also, the mention of “temperature‑controlled cache” is vague; what’s the actual threshold? If you wanted a groundbreaking protocol, you might include redundancy plans. As it stands, it’s a decent reminder, nothing more. Maybe next revision will address these gaps.

King Shayne I

December 29, 2025 AT 09:09Honestly the documennt could use a total revamp – the phrasing is sloppy and the tone is way too casual for a military guidline. Fix it.

Roberta Giaimo

January 4, 2026 AT 20:43Great effort on structuring the checklist; the headings are clear and the steps follow a logical order. :)

Tom Druyts

January 11, 2026 AT 08:16Let’s keep the momentum, troops! Every checked box is a win for the mission.