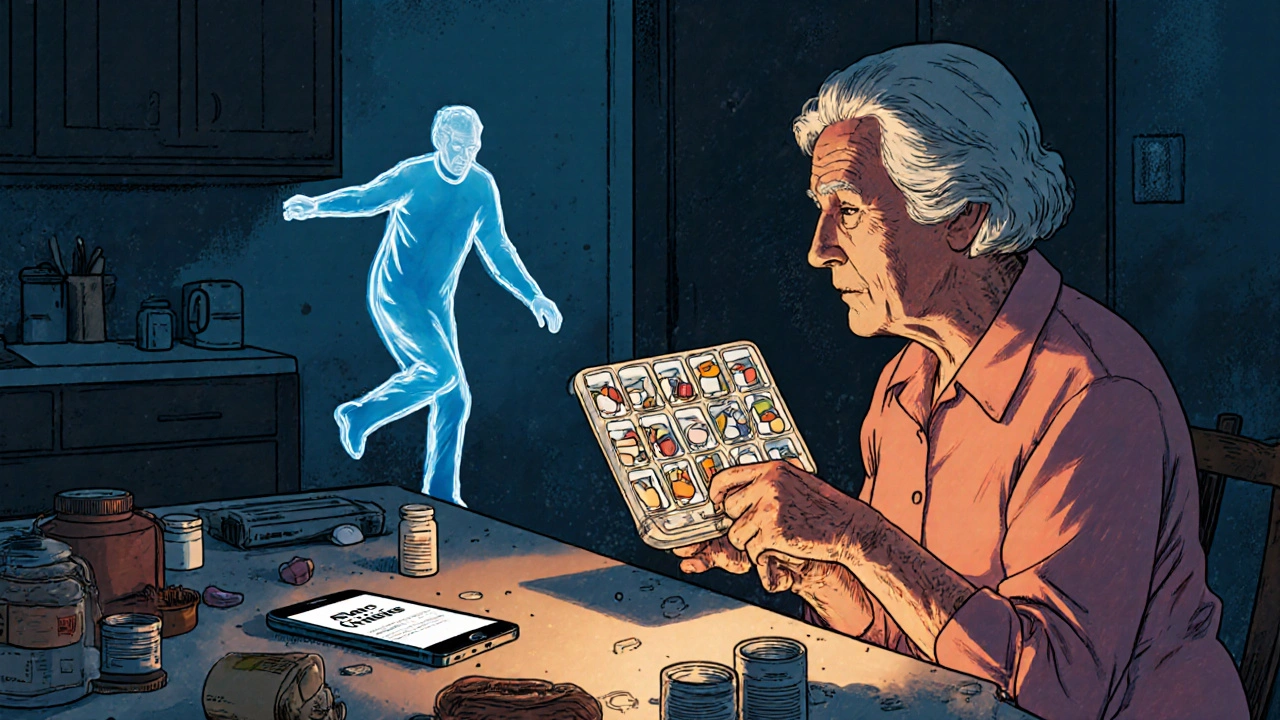

Every year, thousands of older adults end up in the hospital because of a medication that was supposed to help them - but ended up hurting them instead. It’s not always a mistake. Sometimes, it’s because a drug that’s fine for a 40-year-old is risky for someone over 65. That’s where the Beers Criteria come in. They’re not a law. They’re not a punishment. They’re a warning sign - a clear, evidence-based list of drugs that should be avoided or used with extreme caution in older adults.

What Are the Beers Criteria?

The Beers Criteria are a living guide, updated every few years by the American Geriatrics Society (AGS), that identifies medications with higher risks than benefits for people aged 65 and older. First created in 1991 by Dr. Mark Beers, the list has grown and changed as science has advanced. The latest version, published in 2023, includes 131 specific medication criteria. That means over 100 drugs or drug classes flagged as potentially dangerous for seniors - not because they’re all bad, but because their side effects often outweigh their benefits in older bodies.Why does this matter? As we age, our kidneys and liver don’t work as efficiently. Our body fat and muscle ratio changes. Our brain becomes more sensitive to certain chemicals. A drug that’s cleared from a young person’s system in hours might linger for days in an older adult. That’s why a low dose of a sleeping pill, or a common painkiller, can cause falls, confusion, or even kidney failure in someone over 65.

How the Beers Criteria Are Organized

The 2023 update breaks down risky medications into five clear groups:- Medications to avoid in most older adults - These are drugs with high risk and little benefit, no matter what else is going on. Examples include long-acting benzodiazepines like diazepam (Valium), anticholinergics like diphenhydramine (Benadryl), and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) like ibuprofen for long-term use.

- Medications to avoid with specific health conditions - Some drugs are dangerous only if you have certain diseases. For example, antipsychotics like haloperidol or risperidone should almost never be used in people with dementia because they raise the risk of stroke and death. Similarly, certain blood pressure drugs like non-dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers (e.g., diltiazem) can worsen heart failure.

- Medications to use with caution - These aren’t outright banned, but they need close monitoring. Examples include proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) like omeprazole used longer than 8 weeks, or muscle relaxants like cyclobenzaprine, which can cause dizziness and confusion.

- Medications to avoid with kidney problems - Many drugs are cleared by the kidneys. If kidney function is low (common in older adults), these drugs build up. Metformin, for instance, was once avoided entirely in kidney disease, but now it’s used cautiously with strict monitoring - a shift in thinking since the 2019 update.

- Drug interactions to avoid - Some combinations are deadly. For example, combining NSAIDs with diuretics and ACE inhibitors (the "triple whammy") can cause sudden kidney failure. Or mixing SSRIs with tramadol can trigger serotonin syndrome.

Each of these is backed by research - not guesswork. The 2023 panel reviewed over 1,500 studies published between 2019 and 2022. They didn’t just look at side effects. They looked at real outcomes: hospital stays, falls, cognitive decline, and death.

Why These Drugs Are Still Prescribed

You might wonder: if these drugs are so risky, why are they still being given out?Because sometimes, they’re the only option - or the easiest one. A nurse in a nursing home might give a resident diphenhydramine for sleep because it’s cheap, available, and fast-acting. A doctor might prescribe an NSAID for arthritis pain because the patient can’t afford or tolerate a safer alternative. A family might ask for a sleeping pill because their parent isn’t resting.

But here’s the problem: these drugs often become habits. Once started, they’re rarely stopped. And older adults often take five, ten, or even more medications. That’s called polypharmacy. About 40% of seniors are on five or more drugs. And studies show that 20% of them are taking at least one medication flagged by the Beers Criteria.

It’s not always the doctor’s fault. Sometimes, the system pushes for quick fixes. Insurance doesn’t cover alternatives. Electronic health records don’t flag risks. And many clinicians just don’t have the time to dig into every prescription.

What the Beers Criteria Are NOT

It’s critical to understand what the Beers Criteria are not.They are not a blacklist. They are not a rulebook. The American Geriatrics Society is very clear: "The Beers Criteria are not meant to be applied in a punitive manner." They’re not used to deny care. They’re not used to cut off coverage. And they’re not meant to replace clinical judgment.

Imagine a 78-year-old with chronic pain from spinal stenosis. She’s on a low-dose opioid and a muscle relaxant. One of those drugs is on the Beers list. But she’s stable. She’s not dizzy. She’s sleeping. She’s not falling. Her pain is controlled. Would stopping the drug help? Or would it make her life worse?

That’s the real question. The Beers Criteria point out the risks. But they don’t answer whether the benefit is worth it - that’s up to the patient and their care team.

How Clinicians Use the Beers Criteria

Good doctors don’t just check a box. They use the Beers Criteria as a starting point for conversation.Here’s how it works in practice:

- Review all medications - Every 6 to 12 months, go through every pill, patch, and injection the patient is taking.

- Identify red flags - Use the Beers list to spot drugs that don’t belong.

- Ask: Why was this started? - Was it for a short-term issue that never got stopped?

- Look for alternatives - Can a non-drug option work? Can a safer drug be substituted?

- Deprescribe slowly - Never stop a drug cold turkey. Reduce dose, monitor closely, and involve the patient.

Many hospitals and clinics now use electronic health record systems that auto-flag Beers Criteria drugs. Pharmacists run automated reports. Nurses get alerts. But the best tool is still a thoughtful conversation between patient, doctor, and pharmacist.

Tools That Help

You don’t need to memorize 131 drugs. There are tools to make this easier:- The AGS Beers Criteria mobile app - Free, searchable, updated yearly.

- Pocket cards - Available through the American Geriatrics Society for clinicians.

- Healthinaging.org - A simplified version for patients and families.

- Deprescribing guidelines - Developed by the Deprescribing Research Network to help taper off high-risk drugs safely.

These aren’t just for doctors. Caregivers and family members can use them to ask better questions: "Is this still necessary?" "Are there safer options?" "What happens if we stop it?"

The Bigger Picture: Safety Beyond the List

The Beers Criteria are just one piece of the puzzle. Other tools like STOPP-START (which looks at both inappropriate drugs and missed medications) and the AGS’s "5 Steps to Medication Review" help round out the picture.But the real goal isn’t just to avoid bad drugs. It’s to improve quality of life. A 90-year-old with dementia shouldn’t be on antipsychotics just because she’s agitated. A 75-year-old with mild arthritis shouldn’t be on daily ibuprofen because it’s easier than physical therapy. A person with kidney disease shouldn’t be on a drug that could crash their function.

Medication safety isn’t about eliminating all drugs. It’s about using the right ones, at the right dose, for the right reason - and stopping what’s no longer needed.

What’s New in the 2023 Update

The 2023 version made several key changes:- Stronger warnings on antipsychotics - Even low doses are now flagged as dangerous in dementia patients.

- Expanded guidance on benzodiazepines - These are now clearly linked to increased fall risk and cognitive decline, even with short-term use.

- New criteria for fall risk - Drugs like trazodone (used for sleep) and certain antidepressants were added because they impair balance.

- Clarified metformin use - It’s now considered safer than before, as long as kidney function is monitored.

These updates reflect real-world data. Studies show that when these drugs are reduced or stopped, falls drop by up to 30%. Confusion improves. Hospital visits go down.

Final Thoughts: A Tool, Not a Trap

The Beers Criteria are powerful - not because they’re perfect, but because they make us pause. They force us to ask: "Is this really helping?"They’re used by Medicare, nursing homes, and pharmacies across the U.S. and beyond. But they’re not meant to be rigid. A good clinician uses them as a guide, not a cage. A good patient uses them as a conversation starter.

Older adults deserve medications that improve their lives - not ones that steal their balance, memory, or independence. The Beers Criteria are a roadmap to safer prescribing. But the journey? That’s up to the people involved.

Are all drugs on the Beers Criteria banned for older adults?

No. The Beers Criteria list drugs that carry higher risks for older adults, but they’re not absolute bans. Some medications on the list may still be appropriate for certain individuals - for example, if no safer alternative exists or if the benefits clearly outweigh the risks. The key is individualized decision-making with the patient and their care team.

Can the Beers Criteria be used to deny Medicare coverage?

No. The American Geriatrics Society explicitly states that the Beers Criteria should never be used to restrict health coverage or deny care. While Medicare and Medicaid use the list to measure quality of care in nursing homes and clinics, it’s not a tool for denying prescriptions. Its purpose is education and safety - not cost-cutting.

How often are the Beers Criteria updated?

The American Geriatrics Society updates the Beers Criteria every three to four years. The most recent version was published in 2023, based on a review of over 1,500 scientific studies from 2019 to 2022. Updates ensure the list stays current with new evidence and changing prescribing patterns.

What’s the difference between Beers Criteria and STOPP-START?

The Beers Criteria focus only on potentially inappropriate medications to avoid. STOPP-START looks at both inappropriate prescriptions (STOPP) and important medications that are missing (START). So while Beers helps you stop bad drugs, STOPP-START also helps you start good ones. Many clinicians use both together.

Can family members use the Beers Criteria to talk to doctors?

Yes. The American Geriatrics Society offers simplified versions of the Beers Criteria at healthinaging.org for patients and families. You can bring a printed list or ask: "Is this medication on the Beers list? Are there safer alternatives? Can we try reducing or stopping it?" Being informed helps you be a better advocate.

Next Steps for Patients and Caregivers

If you or a loved one is over 65 and taking multiple medications:- Ask your pharmacist to do a full medication review - it’s free and often covered by insurance.

- Bring a list of every pill, supplement, and patch to every doctor visit.

- Ask: "Is this still needed?" and "What happens if we stop it?"

- Use the free Beers Criteria app to check any new prescription.

- Don’t stop a drug without talking to your provider - some medications need to be tapered.

Medication safety isn’t about fear. It’s about awareness. The Beers Criteria give you the facts. Now it’s up to you to use them wisely.

Sridhar Suvarna

November 18, 2025 AT 16:48Been using this list with my elderly patients in Mumbai for years. Simple, clear, saves lives. No fluff, just facts. If a drug’s on Beers, we pause. Always. No exceptions.

Joseph Peel

November 20, 2025 AT 07:03The 2023 update’s inclusion of trazodone under fall risk is long overdue. A 2021 JAMA study showed a 27% increase in falls among seniors on trazodone versus placebo. This isn’t anecdotal-it’s epidemiological.

Kelsey Robertson

November 21, 2025 AT 14:43Oh, here we go again-another ‘expert’ list that tells doctors what to do… while ignoring the fact that 80% of these patients are on 12+ meds because their ‘holistic’ doctors keep adding ‘natural’ supplements that interact worse than NSAIDs! The Beers Criteria? More like the ‘Bureaucrats’ Criteria.’

Joseph Townsend

November 22, 2025 AT 20:14Bro. I saw my grandma on Benadryl for ‘sleep’ for 12 years. One day she started talking to the TV like it was her dead husband. We pulled it. She remembered her own name within a week. The Beers list? It’s not a list-it’s a lifeline. I’m printing it out and taping it to my doctor’s forehead.

Bill Machi

November 23, 2025 AT 04:15Why are we even talking about this? In America, we have a duty to preserve the sanctity of pharmaceutical innovation. These guidelines are just socialist overreach dressed in medical jargon. If an old man wants to take five sleeping pills and a muscle relaxant, let him. It’s his body, his choice, his funeral.

Elia DOnald Maluleke

November 24, 2025 AT 21:20Here in South Africa, we see this daily. A man, 78, on five drugs, one of them a diuretic he’s been on since 1999. His kidneys? Crumbling. The system doesn’t ask why-he just gets the script. The Beers Criteria are not a suggestion. They are a mirror. And we, as healers, must look into it-no matter how ugly the reflection.

satya pradeep

November 25, 2025 AT 03:39bro the metformin thing changed? i thought it was banned for kidney issues? my uncle got taken off it last year and now he’s on insulin and losing weight like crazy. this list is legit. gotta check all scripts now. saved my dad from a fall too. benadryl = bad news

Prem Hungry

November 25, 2025 AT 19:46Dear friends, let us remember that aging is not a disease, but a journey. The Beers Criteria are not a weapon, but a lantern. Use them with compassion, not fear. Every pill you remove is a step toward dignity. Let us tread gently, but surely.

Leslie Douglas-Churchwell

November 27, 2025 AT 03:50⚠️ BIG RED FLAG: Did you know the AGS is secretly funded by Big Pharma? The 2023 update removed 12 drugs from the list… all of which were generics. Coincidence? Or a backdoor to push expensive brand-name alternatives? The Beers Criteria are a Trojan horse. Check the funding. Check the conflicts. This isn’t medicine-it’s market control. 🧠💊 #WakeUp

shubham seth

November 28, 2025 AT 22:59Let’s be real-the Beers list is just a glorified ‘don’t be dumb’ checklist. The real problem? Doctors who think ‘prescribe and forget’ is a clinical strategy. Half the people on these meds don’t even know what they’re for. If your grandpa’s on a muscle relaxant for ‘back pain’ and hasn’t moved in 3 months… you’re not managing care. You’re just collecting prescriptions.

henry mariono

November 30, 2025 AT 03:29I’ve been a geriatric nurse for 22 years. The Beers Criteria saved me from making a fatal mistake once. I didn’t question them. I just listened. Sometimes the quietest advice is the most vital.

Jeremy Hernandez

November 30, 2025 AT 14:21LOL the ‘de-prescribe slowly’ part? That’s just code for ‘we don’t want to deal with angry patients.’ Just cut the crap. If it’s on the list, yank it. No gradual nonsense. People don’t need to be coddled-they need to be saved.

Tarryne Rolle

December 1, 2025 AT 01:33It’s funny how the same people who scream about autonomy when it’s about abortion suddenly want to micro-manage what elderly people take. The Beers Criteria are just the first step toward state-controlled medicine. Next, they’ll tell us how to breathe.

Kyle Swatt

December 2, 2025 AT 14:28My 84-year-old aunt was on a cocktail of benzodiazepines and NSAIDs. We tapered her off over 8 weeks. She started reading novels again. Remembered her granddaughter’s birthday. She didn’t need more drugs-she needed to be heard. The Beers Criteria don’t tell you what to do. They remind you to ask why.