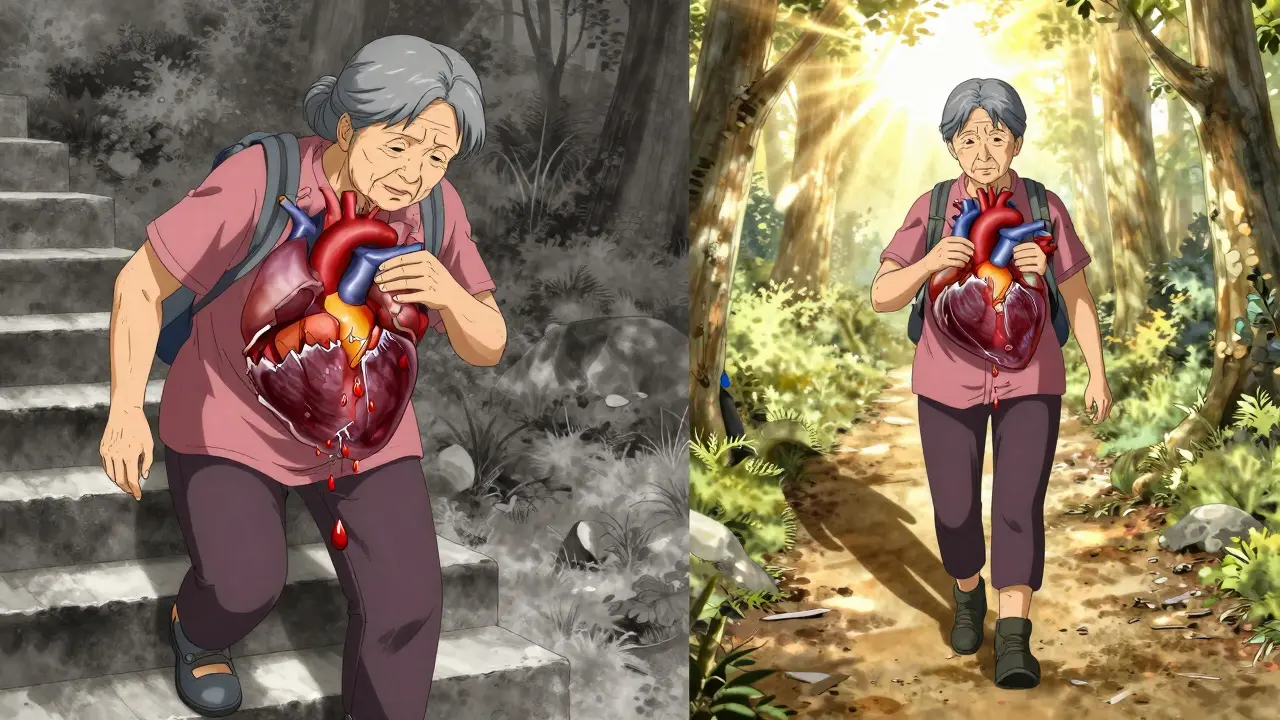

When your heart valve doesn’t open or close right, your whole body feels it. You might not notice at first-just a little shortness of breath climbing stairs, or feeling tired after walking the dog. But if a valve is narrowed or leaking, your heart is working overtime. Left untreated, this can lead to heart failure, irregular rhythms, or even sudden death. The good news? We know exactly how to fix it-and the options today are better than ever.

What Happens When Heart Valves Fail

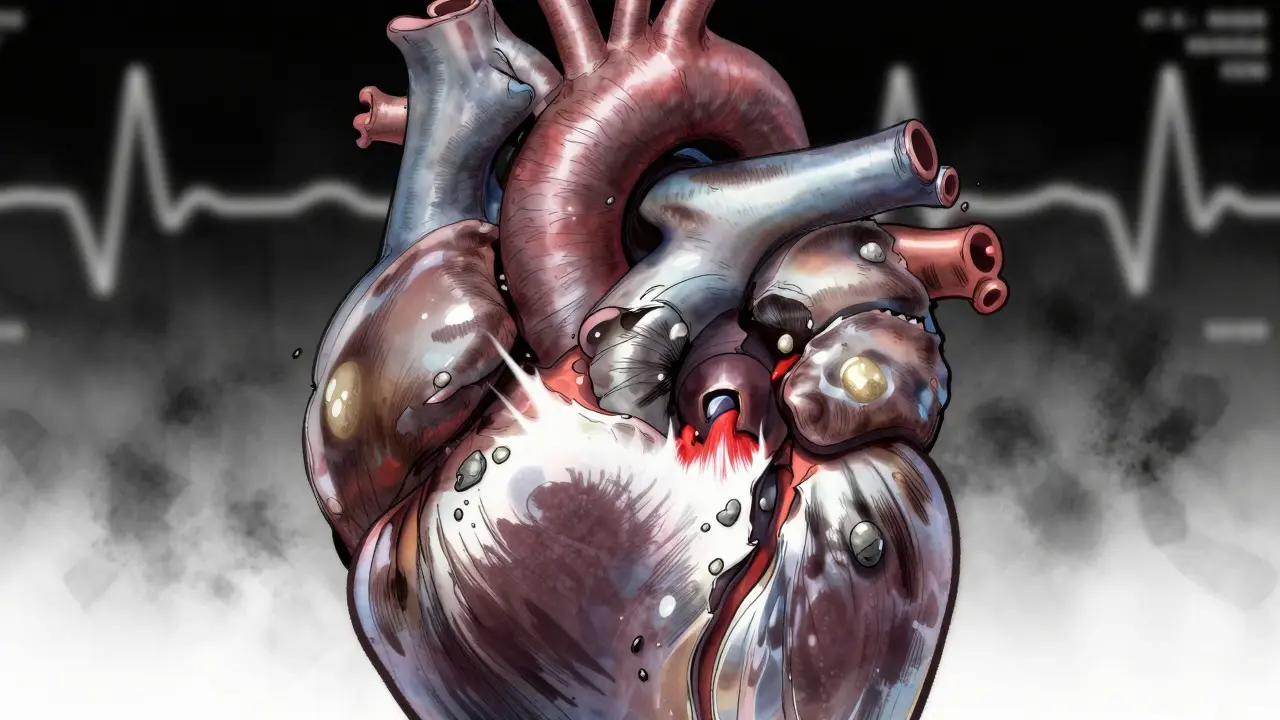

Your heart has four valves: aortic, mitral, tricuspid, and pulmonary. They’re like one-way doors that open to let blood flow forward and snap shut to stop it from flowing backward. When they work right, blood moves smoothly through your heart and out to your body. But when they don’t, two main problems happen: stenosis and regurgitation.Stenosis means the valve opening is too narrow. It’s like trying to squeeze through a door that’s been half-blocked. The heart has to pump harder to push blood through. Regurgitation is the opposite-the valve doesn’t close tightly, so blood leaks backward. It’s like a faulty faucet that drips even when turned off. Both force your heart to work harder, and over time, that strain weakens it.

Aortic stenosis is the most common serious valve problem in older adults. About 2% of people over 65 have it, mostly because calcium builds up on the valve leaflets as they age. In younger people, it’s often caused by a bicuspid aortic valve-a birth defect where the valve has only two leaflets instead of three. Mitral stenosis is rarer in places like Australia and the U.S., but still common in developing countries, where it’s usually caused by rheumatic fever from untreated strep throat decades earlier.

Regurgitation can hit any valve, but mitral and aortic are the most frequent. Mitral regurgitation happens when the valve between the left atrium and ventricle leaks. Blood flows back into the lung circulation, causing fluid buildup. Aortic regurgitation lets oxygen-rich blood flow back into the heart instead of out to the body. That makes the heart swell and pump inefficiently.

How Doctors Spot the Problem

Most valve problems are found during a routine checkup. A doctor hears a murmur-a whooshing or clicking sound-through a stethoscope. That’s the first clue. But to know how bad it is, you need an echocardiogram. This ultrasound of the heart shows the valve’s shape, how wide it opens, how much blood leaks, and how hard the heart is working.For aortic stenosis, doctors look at three key numbers:

- Valve area: Less than 1.0 cm² means severe stenosis

- Pressure gradient: Over 40 mmHg means the heart is struggling

- Jet velocity: Faster than 4.0 m/s signals serious narrowing

For mitral stenosis, the valve area must be below 2.5 cm² to be considered abnormal, and below 1.5 cm² for severe cases. Regurgitation is graded from mild to severe based on how much blood flows backward. The bigger the leak, the more the heart has to compensate.

Symptoms don’t always match how bad the valve damage is. Some people with severe stenosis feel fine until they suddenly collapse. Others with mild regurgitation get winded climbing one flight of stairs. That’s why regular monitoring matters-even if you feel okay, your heart might be quietly failing.

Stenosis vs. Regurgitation: Key Differences

It’s easy to mix up stenosis and regurgitation, but they affect the heart in opposite ways.

Stenosis is about pressure. The heart has to generate high pressure to force blood through a tight valve. That thickens the heart muscle, especially the left ventricle. Over time, the muscle stiffens and can’t relax properly. Patients often feel chest pain, get dizzy when standing up, or pass out during activity. The classic triad: angina, syncope, and heart failure-shows up in about half of severe cases.

Regurgitation is about volume. The heart has to pump extra blood because some leaks back. That makes the chamber enlarge. Patients feel tired, short of breath when lying flat, or notice their heart racing. They might not realize it’s a valve problem until their chest X-ray shows an enlarged heart.

Mitral stenosis mostly causes lung congestion: coughing at night, needing extra pillows to sleep, swelling in the legs. Mitral regurgitation is sneakier-it often causes fatigue for years before anything else shows up. That’s why many people are diagnosed late, after their heart is already damaged.

Surgical and Non-Surgical Options

Not every valve problem needs surgery. Mild cases are monitored with yearly echos. But when it gets severe, intervention becomes life-saving. For aortic stenosis, untreated patients have only a 50% chance of living five years. With valve replacement, that jumps to 85%.

Here’s what’s available today:

1. Balloon Valvuloplasty

This is a quick fix for mitral stenosis, especially in younger patients or those too sick for surgery. A balloon is threaded up from the leg into the heart and inflated to crack open the stiff valve. It takes about 90 minutes, and most people go home in two days. But it’s not permanent-about half the patients need another procedure within five years.

2. Surgical Valve Replacement

This is the gold standard for severe cases. The damaged valve is removed and replaced with either a mechanical valve or a tissue valve (from a pig, cow, or human donor). The surgery takes 3-4 hours. Recovery is tough: sternotomy pain lasts 6-8 weeks, and you can’t lift heavy things for months.

But the results last. Mechanical valves last forever, but you’ll need blood thinners for life. Tissue valves don’t need lifelong anticoagulation, but they wear out in 15-20 years. For people over 70, tissue valves are usually preferred because they’re less risky long-term.

3. Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement (TAVR)

TAVR is the biggest revolution in heart valve care in 20 years. Instead of opening the chest, a new valve is delivered through a catheter in the leg or chest. It’s done under local anesthesia. Most patients go home in 2-3 days. By 2023, over 65% of aortic valve replacements in the U.S. for patients over 75 were done with TAVR.

It’s no longer just for high-risk patients. Recent trials show TAVR works just as well as open surgery for low-risk patients aged 60-80. Survival rates at two years are nearly identical: 89.5% for TAVR, 88.4% for surgery.

4. Transcatheter Mitral Repair

For mitral regurgitation, especially if it’s caused by a weakened heart (functional regurgitation), the MitraClip device can be used. It clips the leaflets together to reduce the leak. The COAPT trial showed it cuts death risk by 32% compared to medicine alone. For primary mitral regurgitation (due to valve damage), surgery still gives better long-term results-90% survive 10 years after repair versus 75% with meds.

What Recovery Really Looks Like

People think valve surgery means a quick fix. It’s not. Recovery takes time. After TAVR, most feel better in days. After open-heart surgery, it’s weeks to months.

One patient in Cleveland’s registry said, “I went from struggling to walk to the mailbox to hiking 3 miles in two months.” But another shared, “The hardest part was lifting my grandchildren. I couldn’t do it for eight weeks.”

Anticoagulation is another big part of recovery. If you get a mechanical valve, you’ll need blood thinners like warfarin. That means regular INR checks-twice a week at first, then monthly. Too thin, and you risk bleeding. Too thick, and you risk a clot. It’s a balancing act.

Many patients report feeling dismissed until symptoms became severe. One survey found 28% of people didn’t get proper care until they were near collapse. That’s why if you’re over 65 and feel unusually tired, get checked. Don’t wait.

What’s Coming Next

The future of valve care is minimally invasive. The FDA approved the Evoque valve for tricuspid regurgitation in 2023-something that didn’t exist five years ago. The Cardioband system, which tightens the valve ring without open surgery, is now approved in Europe and in U.S. trials.

Tissue engineering is advancing fast. New bioprosthetic valves are being made with materials that resist calcification better. One study predicts next-gen valves could last 25+ years, making them viable for patients under 60.

By 2030, experts predict 80% of valve procedures will be done through catheters. That means less pain, faster recovery, and more people getting treated before their hearts break down.

The message is clear: Valve disease isn’t just an old person’s problem. It’s a treatable condition-and the tools to fix it are better than ever. If you’ve been told you have a heart murmur, don’t ignore it. Get the echo. Know your numbers. And don’t wait for symptoms to get worse before acting.

Can you live with a leaky heart valve without surgery?

Yes, many people live with mild or moderate valve regurgitation for years without surgery. Doctors monitor them with regular echocardiograms and manage symptoms with medication. But if the leak becomes severe or the heart starts to enlarge, surgery becomes necessary to prevent irreversible damage. Waiting too long can reduce survival chances.

Is TAVR better than open-heart surgery?

For patients over 75 or those with other health issues, TAVR is usually better-it has lower risk, faster recovery, and similar long-term survival. For younger, healthier patients under 65, open surgery may still be preferred because mechanical valves last longer. But recent data shows TAVR is now just as effective for low-risk patients up to age 80.

How do I know if my valve problem is serious?

Symptoms like shortness of breath during light activity, chest pain, dizziness, or swelling in the legs are red flags. But sometimes, the worst cases have no symptoms. The real test is an echocardiogram. If your aortic valve area is under 1.0 cm², or your mitral regurgitation is severe, you’re in the danger zone-even if you feel fine.

Do I need to take blood thinners forever after valve replacement?

Only if you get a mechanical valve. Those require lifelong blood thinners like warfarin to prevent clots. Tissue valves (from animals or donors) don’t usually need long-term anticoagulation, though you may need it for a few months after surgery. Your doctor will monitor your INR levels and adjust based on your valve type and other health factors.

Can lifestyle changes fix a bad heart valve?

No. Diet, exercise, and quitting smoking won’t fix a narrowed or leaking valve. But they can help your heart stay stronger while you wait for treatment. They also reduce other risks like high blood pressure and cholesterol, which make valve disease worse. Lifestyle changes support treatment-they don’t replace it.

Priya Patel

January 11, 2026 AT 01:45Wow, this is such a clear breakdown. I had no idea mitral regurgitation could sneak up on you for years without symptoms. My grandma was diagnosed last year after she started needing three pillows to sleep - turns out her valve was leaking bad. She got the MitraClip and now she’s gardening again. Life-changing.

Priscilla Kraft

January 12, 2026 AT 06:47Thank you for writing this. So many people think heart murmurs are just ‘part of aging’ - but nope. My dad ignored his for 5 years because he ‘felt fine.’ By the time he got the echo, his LV was enlarged. TAVR saved him. Don’t wait. Get checked. 💙

Sean Feng

January 12, 2026 AT 16:50So basically if you’re over 65 and tired, just assume you need a new valve? Seems like a cash grab to me.

Alfred Schmidt

January 14, 2026 AT 03:12Are you serious? You’re telling people to get an echo because they’re ‘tired’? That’s like saying if you’re out of breath after walking to the fridge you need open-heart surgery. This article is alarmist nonsense. Most people don’t need intervention until their EF drops below 35% - and even then, meds come first. Stop scaring people.

Michael Patterson

January 14, 2026 AT 23:32Okay so I read this whole thing and I’m still confused. Like, is TAVR better? Or is surgery? And what about the difference between primary and functional regurgitation? And why do some valves wear out and others don’t? Also, I think the part about calcium buildup being from aging is oversimplified - I read a paper last year that said it’s actually linked to chronic inflammation and vitamin K2 deficiency, not just ‘getting old.’ Also, why do they always use pig valves? Don’t cows have bigger ones? And what about the ethical implications of using animal tissue? Also, I think the author is ignoring the role of gut microbiome in valve calcification. I’ve been researching this for 18 months and I think I know more than the cardiologists. Also, I typed this with one hand because I’m holding my coffee and also my dog is barking.

Matthew Miller

January 16, 2026 AT 19:53Another feel-good medical article pushing expensive tech. TAVR is a profit machine for hospitals. The 89.5% survival rate? That’s at 2 years. What about 10? Where’s the long-term data? And don’t get me started on the anticoagulation nightmare for mechanical valves. You think warfarin is easy? Try living with INR checks every week while your insurance drops coverage. This is not a ‘fix.’ It’s a lifetime of bureaucracy.

Jennifer Littler

January 18, 2026 AT 02:29Valve area <1.0 cm² = severe aortic stenosis - confirmed by current ACC/AHA guidelines. Jet velocity >4.0 m/s is a Class I indication for intervention. The COAPT trial data for MitraClip in functional MR is practice-changing. That said, surgical repair remains superior for primary MR with favorable anatomy. Monitoring with serial echo and NT-proBNP is critical in asymptomatic severe cases. The shift toward transcatheter approaches is inevitable - but patient selection remains key. Don’t confuse accessibility with appropriateness.

Jason Shriner

January 19, 2026 AT 04:14So let me get this straight… you’re telling me I can get a new heart valve through my leg… and it’s basically like upgrading my car’s transmission without opening the hood? Cool. But I still have to take blood thinners? So I’m basically a cyborg now? Just say it: I’m a walking medical experiment. 😐

Adewumi Gbotemi

January 20, 2026 AT 16:59This is very good. In Nigeria, many people die because they don’t know what a murmur is. They think it’s spirit. Now I will share this with my village. Thank you.

Madhav Malhotra

January 21, 2026 AT 22:01Back home in India, we still see a lot of rheumatic heart disease from untreated strep. My cousin had mitral stenosis at 28 - because her mom never took her to the doctor for that sore throat in 1995. This article is a lifeline for places like ours. TAVR might be fancy, but we need cheap echos and antibiotics first. Thanks for the clarity.