CF-Asthma Bronchodilator Response Calculator

Enter FEV1 values from pulmonary function test to calculate bronchodilator response percentage. A response of 12% or more indicates an asthma component in CF patients according to clinical guidelines.

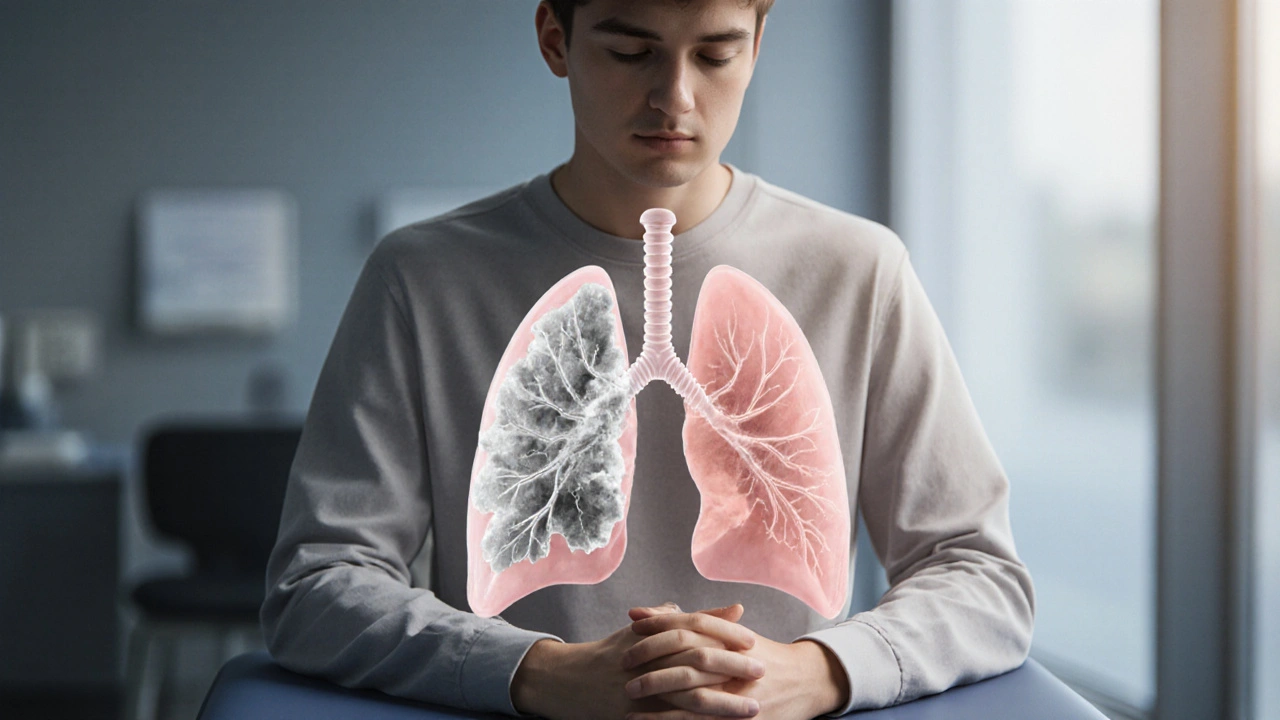

Ever wondered why some people with Cystic Fibrosis a genetic disease that blocks the lungs and pancreas with thick, sticky mucus also complain of wheezing, cough, and shortness of breath? It’s not a coincidence - the two conditions share a tangled web of symptoms, genetics, and inflammation. This guide untangles the science, points out the red‑flags, and shows how to treat both without over‑medicating.

What Is Cystic Fibrosis?

CF (Cystic Fibrosis) is caused by mutations in the CFTR gene. The gene normally produces a protein that regulates salt and water movement across cell membranes. When the protein doesn’t work, mucus becomes thick and hard to clear, leading to chronic lung infections, pancreatic insufficiency, and a shortened life expectancy.

Key clinical tools include the Sweat Chloride Test a diagnostic test that measures salt concentration in sweat; values above 60mmol/L confirm CF in most cases and genetic panels that pinpoint the specific mutation (over 2,000 have been identified). Common symptoms are daily cough, frequent lung infections, salty‑tasting skin, and poor growth.

How Asthma Affects the Lungs

Asthma a chronic inflammatory disorder of the airways that causes reversible airflow obstruction is driven by hyper‑responsive bronchial muscles, allergic triggers, and an over‑active immune system. People with asthma experience wheeze, chest tightness, and sudden shortness of breath, especially after exposure to pollen, dust mites, or cold air.

Doctors track severity with Pulmonary Function Test spirometry that measures forced expiratory volume (FEV1) and helps gauge airway obstruction. Inhaled Corticosteroids anti‑inflammatory meds delivered via a puff or nebuliser and short‑acting Bronchodilators drugs that relax airway muscles for quick relief form the backbone of treatment.

Overlapping Symptoms: Why They’re Easy to Mistake

Both diseases cause chronic cough, mucus production, and wheezing, which makes it hard for patients and even clinicians to tease them apart. The biggest clue lies in the pattern:

- CF cough is usually persistent, night‑time, and accompanied by foul‑smelling sputum.

- Asthma wheeze tends to flare after specific triggers and improves quickly with a bronchodilator.

When a CF patient reports sudden, reversible wheeze that eases after using a rescue inhaler, that’s a signal that asthma‑like airway hyper‑responsiveness is at play.

Does Having CF Increase Asthma Risk?

Large cohort studies from the US Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (2023) found that about 15‑20% of people with CF also meet diagnostic criteria for asthma. The risk is higher in children under 12, likely because their airways are still developing and are more prone to allergic sensitisation.

Genetically, the CFTR mutation does not directly cause asthma, but the chronic inflammation and mucus plugging in CF create an environment where bronchial hyper‑responsiveness can sprout. Think of it as a “second‑hand” effect: the lungs are already damaged, so they over‑react to any irritant.

Shared Biological Pathways

Both conditions involve airway inflammation, but the cellular players differ slightly:

- CF: neutrophil‑dominant inflammation, high levels of IL‑8, and persistent bacterial colonisation (Pseudomonas aeruginosa).

- Asthma: eosinophil‑driven inflammation, elevated IL‑4, IL‑5, and IgE‑mediated allergic responses.

Interestingly, recent research shows that neutrophil‑derived enzymes in CF can also amplify eosinophilic pathways, blurring the line between the two diseases. This cross‑talk explains why some CF patients benefit from asthma‑specific therapies like inhaled corticosteroids, even though traditional CF care focuses on antibiotics and airway clearance.

Managing Both Conditions Together

When a clinician suspects coexistence, the treatment plan needs to balance two goals: clear the thick CF mucus *and* control asthma’s hyper‑responsiveness. Here’s a practical roadmap:

- Confirm diagnosis: Perform spirometry with bronchodilator response, check allergy panels, and repeat sweat chloride if needed.

- Optimise airway clearance: Use chest physiotherapy, high‑frequency chest wall oscillation, or a vibratory vest to move CF mucus.

- Target inflammation: Add low‑dose inhaled corticosteroids if the bronchodilator response is ≥12% improvement in FEV1.

- Control triggers: Keep a home allergen diary, use HEPA filters, and avoid tobacco smoke.

- Leverage CFTR modulators: Drugs like ivacaftor‑tezacaftor‑elexacaftor improve mucus hydration, indirectly reducing asthma‑like symptoms.

- Monitor closely: Track exacerbations, lung function, and side‑effects at least quarterly.

Patients often wonder whether adding a steroid will hurt their CF lung health. In practice, the low‑dose inhaled form stays mostly in the airway, delivering anti‑inflammatory action without the systemic risks seen with oral steroids.

Latest Research and Treatment Options

The biggest breakthrough in the last five years has been the rise of CFTR Modulators small‑molecule drugs that correct the underlying protein defect in CF. Studies published in 2024 show that patients on triple therapy (elexacaftor/tezacaftor/ivacaftor) experience a 30% reduction in asthma‑type wheeze episodes compared to historic controls.

On the asthma front, biologics such as dupilumab (an IL‑4/13 blocker) are being trialled in CF cohorts with promising results: reductions in eosinophil counts and fewer rescue inhaler uses. While not yet standard care, these trials hint at a future where personalised biologics treat the overlapping inflammation.

For home care, smart nebulisers that sync with mobile apps now provide real‑time adherence data. When linked to a CF clinic’s telehealth portal, physicians can tweak inhaled therapy before an exacerbation snowballs.

Quick Reference Table: CF vs Asthma

| Feature | Cystic Fibrosis | Asthma |

|---|---|---|

| Primary cause | Genetic mutation in CFTR gene | Immune‑mediated airway hyper‑responsiveness |

| Typical mucus | Thick, dehydrated, prone to bacterial colonisation | Thin, eosinophil‑rich, responds to allergens |

| Key diagnostic test | Sweat Chloride Test | Spirometry with bronchodilator reversibility |

| First‑line anti‑inflammatory | CFTR modulators (address root cause) | Inhaled Corticosteroids |

| Rescue medication | Short‑acting Bronchodilators (if asthma component present) | Short‑acting Bronchodilators |

| Long‑term complications | Bronchiectasis, chronic infections, pancreatic insufficiency | Airway remodeling, persistent airflow limitation |

Frequently Asked Questions

Can a person have both cystic fibrosis and asthma?

Yes. About 15‑20% of people with CF meet the clinical criteria for asthma. The overlap is more common in children and often shows up as variable wheeze that improves with a rescue inhaler.

How do doctors differentiate between a CF exacerbation and an asthma attack?

Doctors look at the pattern of response to bronchodilators, perform spirometry, and assess sputum characteristics. A rapid ≥12% rise in FEV1 after a bronchodilator points toward an asthma component, while a thick, purulent sputum suggests a CF infection.

Is it safe to use inhaled corticosteroids in cystic fibrosis?

Low‑dose inhaled steroids act locally in the airways and have minimal systemic side‑effects. In patients with documented asthma or bronchial hyper‑responsiveness, they can reduce wheeze without harming CF lung health.

Do CFTR modulators help with asthma‑like symptoms?

Recent trials indicate that triple therapy (elexacaftor/tezacaftor/ivacaftor) improves mucus hydration, which in turn lowers airway hyper‑responsiveness. Patients report fewer rescue inhaler uses and less nocturnal wheeze.

What lifestyle changes support both conditions?

Stay hydrated, maintain regular chest physiotherapy, avoid tobacco smoke and strong perfumes, keep indoor humidity moderate, and follow an allergen‑reduction plan (dust‑mite covers, air purifiers). Consistent use of prescribed inhalers and modulator therapy completes the regimen.

Understanding the link between cystic fibrosis and asthma empowers patients and clinicians to spot overlapping signs early, choose the right meds, and avoid unnecessary hospital trips. With the right mix of airway clearance, targeted anti‑inflammatories, and modern CFTR modulators, many people navigate both diagnoses and enjoy a much better quality of life.

Tracy O'Keeffe

October 12, 2025 AT 22:13Well, isn’t it just the latest buzzword‑fest that CF and asthma are “linked” like lovers in a rom‑com? The reality is far more tangled – a cascade of neutrophils, IL‑8, and mucus viscosity that simply masquarades as wheeze. You can’t reduce an entire genetic syndrome to a “shared inflammation” hashtag. Moreover, the diagnositc criteria for asthma are wielded like a scalpel on a patient whose lungs are already a battlefield. So before we start preaching “dual therapy”, let’s remember that correlation does NOT equal causation, darling.

Rajesh Singh

October 15, 2025 AT 05:46We live in an age where the allure of “more meds” is almost a religion, and anyone who nods at a cocktail of antibiotics, modulators, and inhaled steroids is basically preaching a gospel of polypharmacy. The first commandment should be “Thou shalt not overwhelm the fragile CF lung with unnecessary bronchodilator bursts.” Yet the literature, draped in euphemisms, constantly tempts clinicians to sprinkle an extra puff of albuterol whenever a wheeze appears, as if the solution to every breathless moment is a quick spray. This mindset ignores the principle that every additional drug adds a layer of risk – oral steroids bring skeletal frailty, high‑dose inhaled steroids can seed oral thrush, and needless antibiotics fuel resistant organisms that haunt patients for life. Furthermore, the pediatric community must resist the siren song of treating every cough as asthma, because doing so steals precious time from addressing the underlying CF infection that fuels the mucus plug. A balanced approach demands rigorous spirometry, documented bronchodilator reversibility, and an allergy panel before labeling a CF patient asthmatic. It also calls for honest conversations with families about the trade‑offs of added medications, respecting their agency rather than imposing a regimen that looks impressive on a chart. The ethical compass points toward minimal effective therapy, not maximal pharmaceutical bravado. In practice, low‑dose inhaled corticosteroids may be justified, but only after confirming a ≥12 % FEV₁ boost post‑bronchodilator – a threshold that is not a suggestion but a hard line. When that line isn’t crossed, the patient’s lungs are better served by intensified airway clearance, CFTR modulators, and vigilant infection control. Moreover, clinicians should champion non‑pharmacologic interventions: humidity control, allergen reduction, and structured physiotherapy, which often achieve more sustainable results than a fourth inhaler. Remember, the ultimate goal is quality of life, not a trophy cabinet of prescriptions. Let us, therefore, wield our medical tools with humility, restraint, and a reverence for the delicate balance inherent in CF airways. Every extra puff without proof is a compromise of trust between doctor and patient. We owe them a treatment plan that respects both science and simplicity.

Albert Fernàndez Chacón

October 16, 2025 AT 09:33I hear you loud and clear – adding meds just for the sake of it can backfire. Keeping the baseline therapy solid while we double‑check bronchodilator response seems like the smartest route. Thanks for laying out the ethical compass so plainly.

Drew Waggoner

October 17, 2025 AT 13:20Reading the drama around “linked” conditions reminds me how often we’re haunted by the fear of missing a diagnosis. The anxiety of potential wheeze can gnaw at patients, leaving them exhausted before the first inhaler even hits the airway.

Mike Hamilton

October 18, 2025 AT 17:06In the grand tapestry of human health, CF and asthma are threads that occasionally intertwine, not because they were designed to dance together, but because the body's response to stress is a universal language. When a genetic defect floods the lungs with viscous mucus, the airway’s own defensive poetry – cytokines, neutrophils, eosinophils – can echo the verses written by allergic triggers. This convergence invites us to reflect on the nature of disease: are we confronting separate entities, or are we witnessing a single story told from different perspectives? The answer may lie in humility, acknowledging that our classifications are tools, not truths. By embracing this mindset, clinicians can craft care plans that honor both the inherited and the acquired battles within each breath.

Matthew Miller

October 19, 2025 AT 20:53Exactly! Let’s channel that insight into action – grab that chest physiotherapy routine, power‑up the CFTR modulators, and sprinkle in a dash of inhaled steroid when the wheeze tries to crash the party. Together we can turn the tide!

Liberty Moneybomb

October 21, 2025 AT 00:40What the hell aren’t they telling us? Big pharma loves the “CF‑asthma” label because it opens a gold mine for patented inhalers and “exclusive” biologics. They push the narrative that you need a cocktail of expensive drugs, while the real cure-clean air, natural herbs, and a rejection of corporate greed-gets buried beneath press releases. Wake up, folks: the system feeds on our fear.

Alex Lineses

October 22, 2025 AT 04:26Hey, I get the frustration, but let’s focus on evidence‑based steps that actually help patients today. Regular allergen mitigation, consistent physiotherapy, and using approved modulators have demonstrated real improvements without succumbing to hype. Keep the dialogue open, and we’ll navigate the landscape together.

Brian Van Horne

October 23, 2025 AT 08:13Confirm bronchodilator response before adding steroids.

Norman Adams

October 24, 2025 AT 12:00Oh brilliant, because every pulmonologist reads that memo before every prescription – sarcasm intended.

Margaret pope

October 25, 2025 AT 15:46We all benefit from sharing experiences and tips it helps everyone feel less alone and more empowered