Every year, thousands of people end up in the hospital with serious liver damage-not from alcohol, not from viruses, but from a common painkiller they didn’t even realize was dangerous in large amounts: acetaminophen. And the biggest risk? It’s not from taking too much Tylenol alone. It’s from mixing prescription painkillers like Vicodin, Percocet, or Norco with over-the-counter cold meds, sleep aids, or other pain relievers that also contain acetaminophen. People think they’re being careful. They take one pill for back pain, another for a headache, maybe a cough syrup at night. But they’re stacking acetaminophen without knowing it-and hitting a toxic dose.

Why Combination Products Are So Dangerous

Acetaminophen is in more than 600 different medications. It’s in prescription opioids like hydrocodone and oxycodone combinations, in cold and flu remedies, in sleep aids like Tylenol PM, and even in some migraine pills. The problem isn’t that acetaminophen is bad-it’s safe when used correctly. The danger comes from the fact that most people don’t know how much they’re taking in total.

Doctors and pharmacists warn about the 4,000 mg daily limit. But here’s the catch: that limit is easy to cross without trying. One Vicodin tablet has 325 mg of acetaminophen. Take four of them in a day? That’s 1,300 mg. Add two extra-strength Tylenol (1,000 mg each)? Now you’re at 3,300 mg. Then you grab a cold medicine with 325 mg more for a stuffy nose? You’ve hit 3,625 mg. And you haven’t even taken your nighttime sleep aid yet. That’s how it happens-slowly, quietly, without any warning signs.

In 2019, a study in Hepatology found that nearly 3 out of 10 cases of acetaminophen-related liver injury in the U.S. came from combination products. And 7 out of 10 of those cases were unintentional. People didn’t mean to overdose. They just didn’t know what they were taking.

The Science Behind the Damage

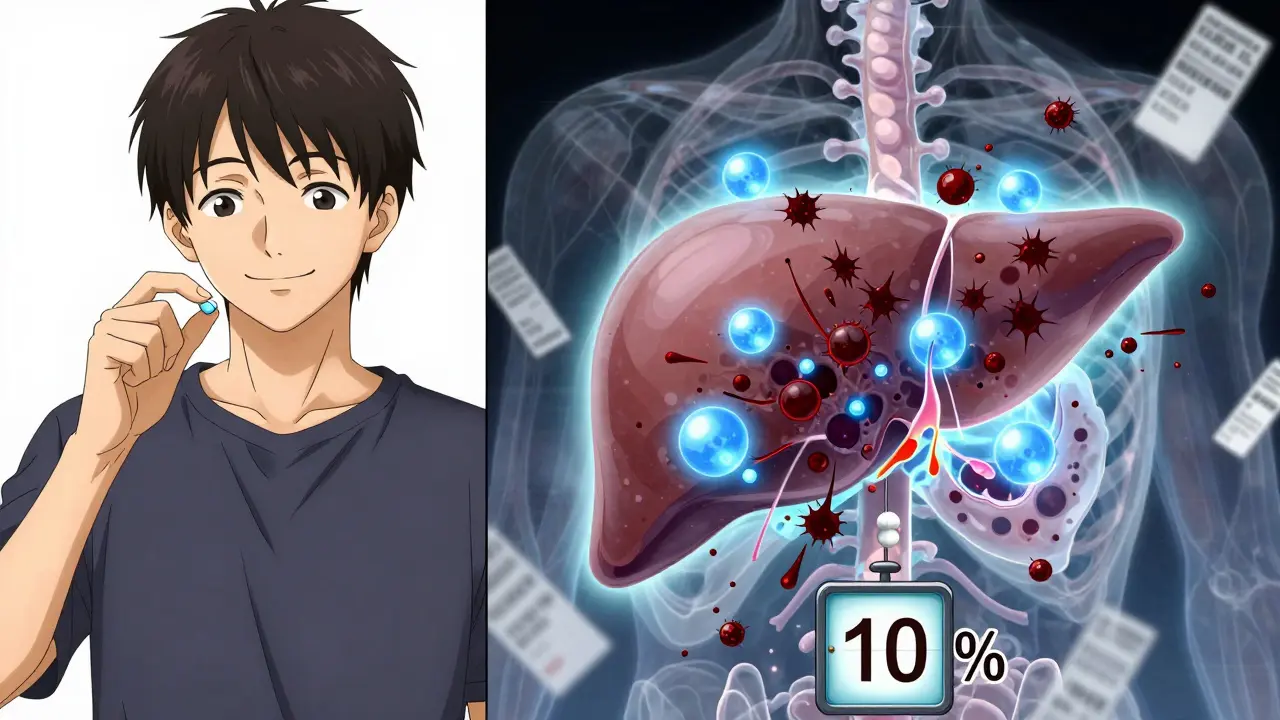

Your liver breaks down acetaminophen using two main pathways: glucuronidation and sulfation. These are safe, normal processes. But when you take too much, those pathways get overwhelmed. Then your liver starts using a third, riskier path that produces a toxic byproduct called NAPQI.

Normally, your liver has enough glutathione-a natural antioxidant-to neutralize NAPQI. But when you overdose, glutathione runs out. Without it, NAPQI starts attacking liver cells. It damages mitochondria, the energy factories inside your cells. That triggers a chain reaction: oxidative stress, inflammation, and eventually, cell death. This isn’t a slow burn. It can happen in just hours.

Research from the Journal of Clinical Investigation showed that once glutathione drops below 30% of normal levels, liver damage becomes likely. And once it hits 10%, the damage can be irreversible. That’s why timing matters so much-if you realize you’ve taken too much, you need help fast.

What the FDA Did-and What’s Still Missing

In 2011, the FDA stepped in. They required that all prescription combination products limit acetaminophen to no more than 325 mg per pill. That rule took full effect by 2014. The goal? To make it harder to hit a dangerous dose with just a few pills.

It helped. Since then, unintentional overdoses from prescription combinations dropped by 29%, according to the Institute for Safe Medication Practices. But the problem didn’t disappear. People are still mixing prescriptions with OTC meds. And many don’t realize that Tylenol, Panadol, and Excedrin all contain acetaminophen.

Even worse, some products still contain 1,000 mg per tablet. The FDA is now considering lowering the OTC maximum to 650 mg per dose. But until that happens, you have to be your own watchdog.

How to Protect Yourself

Here’s what actually works-not guesswork, not warnings you ignore, but clear, actionable steps:

- Read every label, every time. Look for “acetaminophen,” “APAP,” or “paracetamol.” If you see it, add it up. Don’t assume it’s only in the pill you’re taking right now.

- Keep a daily log. Write down every medication you take, including dose and time. Use your phone notes or a small notebook. If you take 325 mg of acetaminophen at 8 a.m., 325 mg at noon, and 325 mg at 6 p.m., you’ve already used 975 mg. That leaves you less than 3,000 mg for the rest of the day.

- Never take two products with acetaminophen at the same time. Even if one is prescription and one is OTC. That’s how most overdoses happen.

- Know your limits. If you drink alcohol regularly, have liver disease, or are underweight, your safe limit is lower-2,000 to 3,000 mg per day. Alcohol and poor nutrition deplete glutathione. You’re more vulnerable.

- Ask your pharmacist. When you pick up a new prescription, ask: “Does this contain acetaminophen?” Don’t assume they’ll tell you unless you ask. Pharmacists are your best line of defense.

What to Do If You Think You’ve Taken Too Much

If you realize you’ve taken more than 4,000 mg in 24 hours-or even 3,000 mg if you’re at higher risk-don’t wait for symptoms. Don’t assume you’ll be fine. Acetaminophen overdose doesn’t cause pain right away. You might feel fine for 24 to 48 hours. Then suddenly, you feel nauseous, tired, or your skin turns yellow. By then, it’s too late for easy fixes.

Go to the ER immediately. Bring all your medications with you. The sooner you get treatment, the better your chances.

The antidote is N-acetylcysteine (NAC). It works by restoring glutathione and protecting your liver. If given within 8 hours of overdose, it’s 90% effective. Even after 24 hours, it still helps. Don’t delay. Call 911 or go straight to the nearest emergency room.

There’s also a new treatment called fomepizole, approved in 2021. It blocks the enzyme that turns acetaminophen into NAPQI. It’s not a replacement for NAC, but it can help in late cases where liver damage is already starting.

What’s Changing on the Horizon

Technology is stepping in. A new smartphone app, currently in beta testing, lets you scan the barcode on any medication and instantly shows your total acetaminophen intake for the day. It works with over 150 combination products and is 89% accurate. That’s not science fiction-it’s coming soon.

Researchers are also testing natural compounds like emodin (from rhubarb) and sulforaphane (from broccoli sprouts) that boost your liver’s own defenses. These aren’t cures, but they might one day be added to medications as protective buffers.

Still, the most powerful tool remains education. A 2018 study in the Annals of Internal Medicine showed that when doctors gave patients a simple, structured talk about acetaminophen risks, unintentional overdoses dropped by 53%. That’s not a small win. That’s life-saving.

Final Reality Check

Most people who overdose on acetaminophen aren’t trying to hurt themselves. They’re just confused. They think, “It’s just Tylenol.” They don’t know it’s in their painkiller. They don’t know their liver can’t handle the pile-up.

But here’s the truth: you don’t need to be a doctor to protect yourself. You just need to be careful. Check labels. Track your doses. Ask questions. Don’t trust your memory. Don’t assume you’re safe because you “only took a few.”

Acetaminophen is one of the most common causes of acute liver failure in the U.S. And nearly half of those cases come from combination products. You can’t control what’s on the shelf. But you can control what you take. And that’s the difference between walking away and ending up in the hospital.

Can I take acetaminophen if I drink alcohol?

If you drink alcohol regularly, your liver’s ability to handle acetaminophen is reduced. Even moderate drinking-three or more drinks a day-can lower your safe limit to 2,000-3,000 mg per day. If you drink often, avoid combination products entirely. The risk of liver damage jumps significantly, even at normal doses.

Is it safe to take acetaminophen for more than a few days?

Taking acetaminophen for more than 10 days in a row-even at recommended doses-can increase liver stress. If you need pain relief longer than that, talk to your doctor. There may be safer alternatives. Long-term use without medical supervision is a red flag.

Do children’s medicines contain acetaminophen?

Yes. Children’s Tylenol, generic fever reducers, and many cold syrups contain acetaminophen. Never give a child more than one product with acetaminophen. Always check the label for the active ingredient. Use the dosing tool that comes with the bottle-not a kitchen spoon.

What if I accidentally took too much but feel fine?

Feeling fine doesn’t mean you’re safe. Liver damage from acetaminophen often shows no symptoms for 24 to 48 hours. If you suspect an overdose-even if you feel okay-go to the ER. Blood tests can detect early liver stress. Waiting for symptoms could cost you your liver.

Are generic brands safer than name brands like Tylenol?

No. Generic brands contain the same active ingredient: acetaminophen. The difference is only in price and inactive fillers. Always check the active ingredient list, not the brand name. Tylenol, Panadol, Excedrin, and store brands all have the same liver risk if taken in excess.

Can I use NAC at home to prevent liver damage?

No. N-acetylcysteine (NAC) is a medical treatment, not a supplement you can take daily to prevent damage. While it’s sold as a supplement, the dose needed to protect against overdose is far higher than what’s available over the counter-and it must be given under medical supervision. Do not self-treat. If you suspect an overdose, go to the hospital.

What Comes Next

If you’re currently taking a combination painkiller, check the label right now. Write down how much acetaminophen is in each pill. Add up what you’ve taken this week. If you’re close to or over 3,000 mg, talk to your doctor. Ask if there’s a non-acetaminophen option.

Set a phone reminder: “Check meds for acetaminophen” every time you refill a prescription. Share this info with family members who take painkillers. You might save someone’s liver-and their life.

evelyn wellding

January 18, 2026 AT 07:38OMG this is so important!! I had no idea my cold medicine had acetaminophen too 😱 I just took two Tylenol and a NyQuil last night and now I’m freaking out… thanks for the wake-up call!! 💪❤️

Bianca Leonhardt

January 19, 2026 AT 07:20People are idiots. You think it’s ‘just Tylenol’ and then you’re in the ER because you can’t read a label. It’s not rocket science. Stop being lazy and check the damn ingredients. Your liver doesn’t care how ‘busy’ you are.

Travis Craw

January 19, 2026 AT 16:20honestly this is the most helpful thing ive read all year. i used to stack my pain meds like candy, never thought twice. now i keep a little note in my phone. thanks for laying it out so simply. 🙏

Riya Katyal

January 20, 2026 AT 18:53Oh wow, so you’re telling me people actually need to *read* labels? Like, in 2024? My grandma could do this. Maybe we should just put a sign on every bottle: ‘DO NOT BE A MORON.’

Henry Ip

January 21, 2026 AT 07:10Love this breakdown. The part about glutathione dropping below 30% is critical. I work in pharmacy and see this way too often. The log tip? Game changer. Start tonight. Write it down. Your future self will thank you.

Corey Chrisinger

January 21, 2026 AT 23:51It’s wild how we treat our bodies like machines that can handle infinite inputs. Acetaminophen isn’t evil-it’s just a molecule. But we forget that biology has limits. The real tragedy isn’t the overdose-it’s that we’re taught to ignore our own systems until they break. Maybe the solution isn’t more warnings… but more humility.

Christina Bilotti

January 23, 2026 AT 19:03Oh wow, a 2018 study showed a 53% drop in overdoses after doctors talked to patients? Shocking. I bet if we just gave people a pamphlet and said ‘read this’ it would work too. /s. Honestly, if you need a 10-step guide to not poisoning yourself, maybe you shouldn’t be medicating at all.

brooke wright

January 24, 2026 AT 14:20I took 5000 mg last week because I had a migraine and a cold and a headache and then a toothache. I felt fine. Still feel fine. But now I’m paranoid. Also my kid’s cough syrup had acetaminophen in it and I didn’t even know. I’m going to throw out half my medicine cabinet. And yes, I’m a mess.