Two kids come home from school with red, crusty sores around their noses. A few days later, their mom wakes up with a swollen, hot patch on her leg that hurts to touch. Both have skin infections-but they’re not the same. One is impetigo, the other is cellulitis. They look similar at first glance, but they’re different in how they spread, how deep they go, and most importantly, how they’re treated.

What Impetigo Really Looks Like

Impetigo is the classic "school sores" infection. It’s everywhere in daycare centers and primary schools, especially in kids aged 2 to 5. You’ll see small red blisters or sores, usually around the nose, mouth, or hands. They don’t stay as blisters for long. Within hours, they burst and leave behind a sticky, honey-colored crust. That’s the hallmark. It’s not usually painful, but it’s incredibly itchy-and contagious.

There are two types: nonbullous (70% of cases) and bullous. Nonbullous is what most people think of-those crusty patches. Bullous impetigo is rarer. It shows up as larger, fluid-filled blisters, 2 to 5 cm across, that look like they’re about to pop. When they do, they leave a thin, ring-like edge. It’s more common in babies and younger children.

What causes it? Mostly Staphylococcus aureus, sometimes Streptococcus pyogenes. These bacteria don’t even need a cut to get in. They can invade healthy skin, especially if it’s dry, irritated from eczema, or already scratched from bug bites. Once one kid has it, it spreads fast-through towels, toys, shared clothing, or even just touching.

What Cellulitis Actually Is

Cellulitis is deeper. It’s not just on the surface. It’s an infection of the dermis and the fatty tissue underneath. You’ll notice a red, swollen, warm, and tender area on the skin-often on the lower legs, but it can happen anywhere. The edges are blurry, not sharp. It doesn’t crust over like impetigo. Instead, the skin might feel tight, look shiny, and sometimes leak clear or yellow fluid.

It’s not just a rash. It’s an infection that’s spreading under the skin. If left untreated, it can move toward the bloodstream, causing fever, chills, and even sepsis. That’s why it’s treated as seriously as it is. Unlike impetigo, cellulitis rarely spreads person-to-person. It usually starts from a break in the skin-a cut, a burn, a fungal infection between the toes, or even a bug bite.

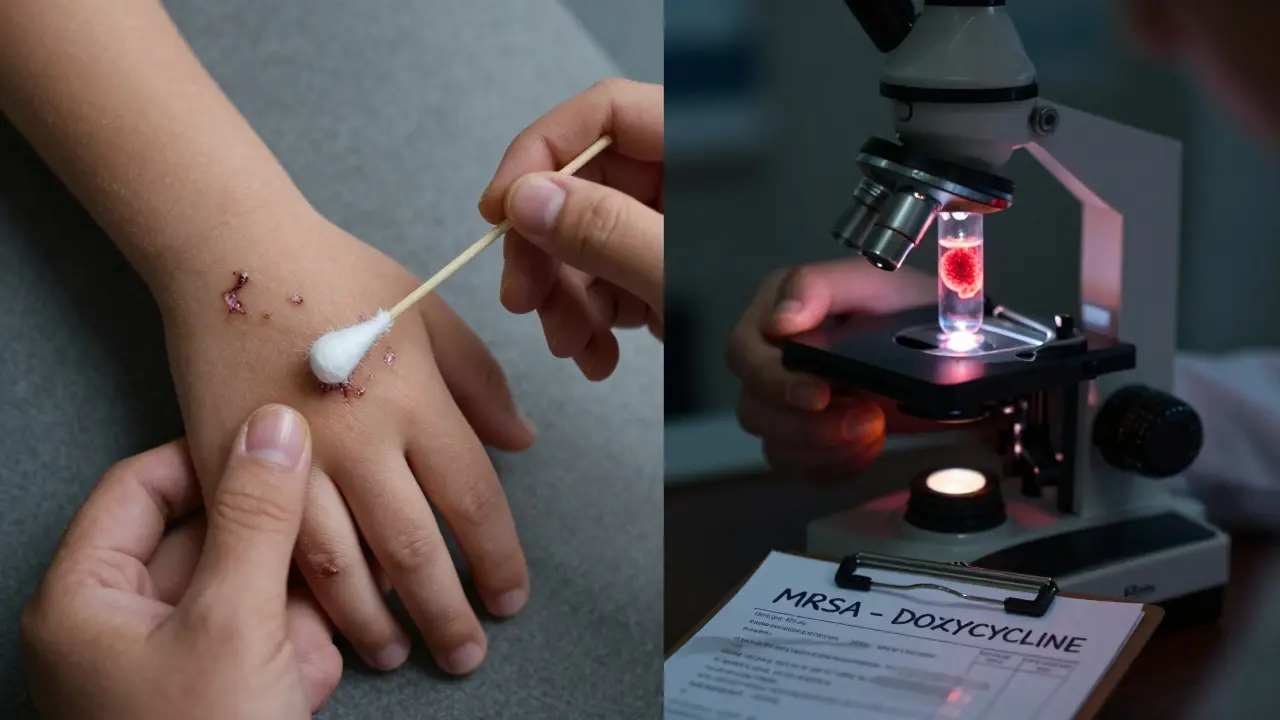

Most cases are caused by Streptococcus bacteria, especially group A Streptococcus. But Staphylococcus aureus is also common. And here’s the twist: more than 30% of cases now involve MRSA-methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. That’s the strain that laughs at regular antibiotics like amoxicillin or flucloxacillin.

Why the Treatment Is Totally Different

You might think, "Both are bacterial skin infections-why not just give the same antibiotic?" But that’s where things go wrong.

For mild impetigo, you don’t even need pills. Topical mupirocin ointment applied three times a day for 7 to 10 days works in about 90% of cases. It’s cheap, targeted, and keeps the infection from spreading. If it’s widespread or not improving, then oral antibiotics like cephalexin or dicloxacillin are used.

Cellulitis? You can’t just rub something on it. It needs to go deep. Oral antibiotics like flucloxacillin, cephalexin, or amoxicillin-clavulanate are standard. But here’s the catch: if you’re in Australia, the UK, or Canada, flucloxacillin is the go-to. In France, doctors often start with amoxicillin. In Belgium, there’s no official guideline-so it’s up to the doctor’s experience.

And if it’s MRSA? Flucloxacillin won’t touch it. You need clindamycin, doxycycline, or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. That’s why doctors are starting to test cultures more often-especially if the infection doesn’t improve after 48 hours, or if the patient has diabetes, a weak immune system, or has been in the hospital recently.

Regional Differences in Antibiotic Use

Antibiotic choices aren’t the same everywhere. In the UK, flucloxacillin prescriptions for cellulitis jumped from 41% to over 51% between 2018 and 2023. In France, amoxicillin use for cellulitis nearly doubled in the same period. For impetigo, the UK and Belgium rely heavily on flucloxacillin-prescriptions climbed to over 80%. But in France, they’re using pristinamycin and amoxicillin-clavulanate more, because resistance to older drugs is rising.

Why the difference? It’s all about local resistance patterns. In some areas, MRSA is rare. In others, it’s everywhere. Doctors in Adelaide, for example, are seeing more MRSA in community-acquired infections than they did five years ago. So they’re starting to think twice before prescribing flucloxacillin for someone who doesn’t improve quickly.

That’s why the best approach isn’t one-size-fits-all. It’s about knowing your community’s bugs. If you’re treating a child with impetigo in a school where 10 kids had it last month, you might skip the culture and just start mupirocin. But if you’re treating an older adult with diabetes and a leg infection that’s getting worse after two days of amoxicillin, you need a culture-and maybe a hospital admission.

When to Worry: Red Flags for Both Infections

Most cases are mild and clear up with treatment. But some turn dangerous fast.

For impetigo, worry if:

- The sores spread rapidly over large areas of the body

- The child develops a fever or seems unusually tired

- The skin around the sores becomes swollen, red, and hot (signs it’s turning into cellulitis)

For cellulitis, the red flags are clearer:

- Fever or chills

- The red area spreads quickly-like 1 cm per hour

- Red streaks running up the leg or arm

- Numbness, tingling, or blistering in the infected area

- Diabetes, poor circulation, or a weakened immune system

If you see any of these, don’t wait. Go to a clinic or ER. Cellulitis can turn into sepsis in under 24 hours if ignored.

Prevention Is Simpler Than You Think

You can’t always avoid these infections, but you can cut the risk big time.

For impetigo:

- Wash hands often-especially after touching sores

- Don’t share towels, bedding, or clothing

- Cover sores with a clean bandage

- Keep kids home for at least 24 hours after starting antibiotics

- Treat eczema well-dry, cracked skin is an open door for bacteria

For cellulitis:

- Clean every cut, scrape, or bite with soap and water

- Apply antibiotic ointment and cover it

- Watch for swelling or redness after injury-don’t ignore it

- If you have diabetes, check your feet daily

- Don’t delay treating athlete’s foot-it can lead to cracks that become infected

And if you’ve had cellulitis before? You’re at higher risk for it again. Doctors may prescribe a low-dose antibiotic long-term to prevent recurrence-especially if you have chronic swelling in your legs.

How Long Does It Take to Get Better?

With the right treatment:

- Impetigo: Crusts start to fade in 3 to 5 days. Sores heal completely in 7 to 10 days.

- Cellulitis: Redness and swelling should improve within 48 to 72 hours. Full recovery takes 5 to 14 days.

If you don’t see improvement in 2 days, call your doctor. That’s the golden window. Delayed treatment means the infection spreads deeper, and you might need IV antibiotics in the hospital.

And don’t stop antibiotics just because it looks better. Finish the full course. Stopping early is how MRSA becomes resistant in the first place.

What About Natural Remedies or Home Treatments?

Some people try tea tree oil, honey, or garlic pastes. There’s no strong evidence they work for impetigo or cellulitis. In fact, using them instead of antibiotics can be dangerous. These infections aren’t like a cold-they don’t get better on their own. Bacteria multiply fast under the skin. Waiting for "natural healing" can mean the difference between a quick fix and a hospital stay.

What does help? Keeping the area clean, dry, and covered. Warm compresses can ease pain from cellulitis. But they don’t kill the bacteria. Antibiotics do.

Can impetigo turn into cellulitis?

Yes, it can. If impetigo isn’t treated or if the skin around the sores becomes swollen, red, and warm, the infection may have spread deeper into the tissue-that’s cellulitis. This is more likely in people with weakened immune systems, eczema, or diabetes. If you notice these signs, seek medical help immediately.

Is cellulitis contagious?

Not directly. You can’t catch cellulitis from someone else like you catch a cold. But if you touch an open wound or sore from someone with cellulitis and you have a cut on your skin, the bacteria could enter your body and cause an infection. That’s why good hygiene and not sharing personal items matters-even with cellulitis.

Do I need a culture test for every skin infection?

No, not for every case. For simple impetigo in a child with no other health issues, doctors usually treat based on appearance. But if the infection doesn’t improve after 2 days, if it’s recurring, if you have diabetes, or if you’ve been in the hospital recently, a culture is recommended. It tells you exactly which bacteria you’re dealing with-and whether it’s resistant to common antibiotics.

Can I use leftover antibiotics from a previous infection?

Never. Antibiotics are prescribed for a specific infection, at a specific dose, for a specific time. Using old antibiotics can be ineffective or even dangerous. You might not be treating the right bacteria, or you might be taking the wrong dose. This also increases the risk of antibiotic resistance. Always get a new prescription.

What’s the best antibiotic for impetigo in kids?

For mild, localized impetigo, topical mupirocin is the first choice. It’s applied three times a day for 7 to 10 days and works in 9 out of 10 cases. If the infection is widespread, oral antibiotics like cephalexin or dicloxacillin are used. Avoid amoxicillin unless the doctor suspects strep involvement. Always complete the full course, even if the sores look gone.

How do I know if it’s impetigo or just a rash?

Impetigo has a very specific look: small sores that turn into honey-colored crusts. It’s rarely itchy at first, but becomes so as it heals. Other rashes-like eczema, ringworm, or allergic reactions-don’t crust over like that. If you’re unsure, take a photo and show it to a doctor. A skin swab can confirm it in minutes.

Can adults get impetigo?

Yes, but it’s less common. Adults usually get it if they have eczema, diabetes, or a weakened immune system. It can also happen after surgery or skin injuries. The treatment is the same as for kids, but doctors are more likely to test for MRSA in adults because resistance is higher in this group.

Should I keep my child home from school with impetigo?

Yes. Most schools and childcare centers require children to stay home until 24 hours after starting antibiotic treatment. This stops the spread to other kids. Even if the sores look better, the bacteria are still active. After 24 hours of antibiotics, the risk of spreading drops dramatically.

Robert Cardoso

January 28, 2026 AT 06:25Let’s cut through the noise: impetigo isn’t ‘school sores’-it’s a public health failure masked as a childhood rite of passage. The fact that we’re still prescribing topical mupirocin as first-line while MRSA rates climb is institutional laziness. This isn’t about antibiotics-it’s about systemic neglect of hygiene infrastructure in low-income schools. You don’t treat symptoms when the environment is the pathogen.

fiona vaz

January 28, 2026 AT 11:02Actually, the data supports mupirocin as first-line for localized cases-even with rising MRSA, it’s still effective against 85% of impetigo strains in community settings. Culture testing is overused in kids without comorbidities. The real issue is parents delaying care until it’s widespread. Early intervention works.

Jeffrey Carroll

January 28, 2026 AT 20:53Thank you for this meticulously researched breakdown. It’s refreshing to see a medical topic presented with both clinical precision and practical clarity. The regional antibiotic variations are particularly illuminating-this kind of context is often missing from guidelines that assume universal applicability.

Bryan Fracchia

January 30, 2026 AT 19:46It’s wild how we treat skin like it’s separate from the body’s whole system. Impetigo and cellulitis aren’t just bugs-they’re signals. One says your hygiene’s slipping, the other says your defenses are down. We fix the ointment, not the person. Maybe we should be asking why kids are scratching so much in the first place. Eczema, stress, diet… we ignore the root because antibiotics are faster.

Katie Mccreary

January 31, 2026 AT 17:16MRSA is a hoax. Big Pharma invented it to sell more drugs. Your kid got impetigo? Put honey on it. Done.

Lance Long

February 2, 2026 AT 02:02My nephew had cellulitis last year. They gave him amoxicillin for 3 days. Nothing changed. Then they switched to clindamycin-within 12 hours, the redness started fading. I swear, if we hadn’t pushed for a culture, he’d have been in the ICU. Don’t wait. Don’t assume. Ask for the test. Your life might depend on it.

Phil Davis

February 3, 2026 AT 20:57So… we’re telling parents to use mupirocin for impetigo, but if their kid has diabetes, suddenly we’re talking MRSA and IV antibiotics? Sounds less like medicine and more like a game of ‘guess which patient is disposable.’

Rose Palmer

February 4, 2026 AT 20:33As a nurse practitioner with 14 years in pediatric dermatology, I can confirm that the 24-hour antibiotic rule before returning to school is not arbitrary-it’s evidence-based. Studies show transmission drops by 92% after this window. The real tragedy is when parents dismiss it as overcaution. This isn’t about bureaucracy; it’s about protecting the immunocompromised child in the next classroom.

Rhiannon Bosse

February 6, 2026 AT 16:39Wait… so if you’re in France, they use pristinamycin? But in the US, we’re still giving flucloxacillin like it’s 2005? This isn’t medicine-it’s a global antibiotic cult. Someone’s getting rich off this. I bet the same lab that sells the tests also sells the pills. And don’t get me started on how they’re hiding the resistance stats from the CDC. It’s all connected.