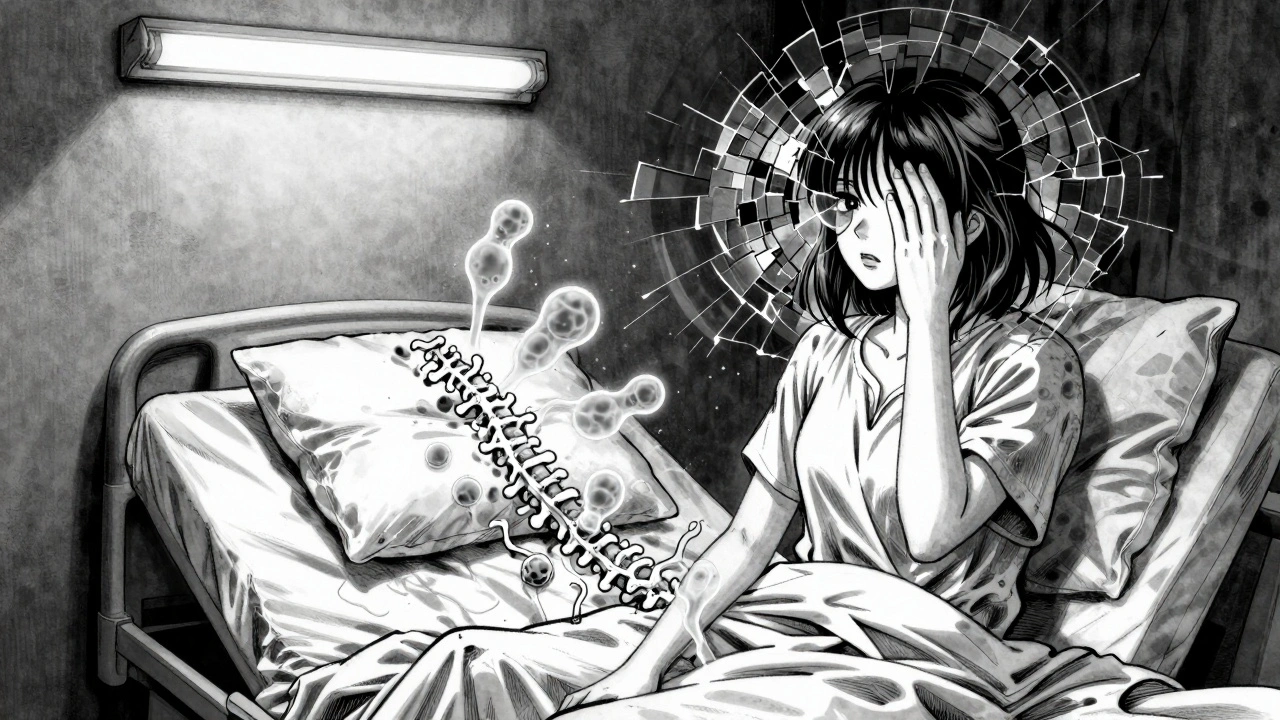

Multiple sclerosis isn’t just a neurological condition-it’s an internal betrayal. Your own immune system, designed to protect you, turns against the very nerves that control your movement, vision, and even your breathing. This isn’t a random glitch. It’s a targeted, chronic attack on the myelin sheath, the protective coating around nerve fibers in your brain and spinal cord. When that coating gets stripped away, signals slow down, misfire, or disappear entirely. The result? Numbness, blurred vision, fatigue so deep it feels like your bones are made of lead, and sometimes, the slow loss of the ability to walk.

What Happens When the Immune System Goes Rogue

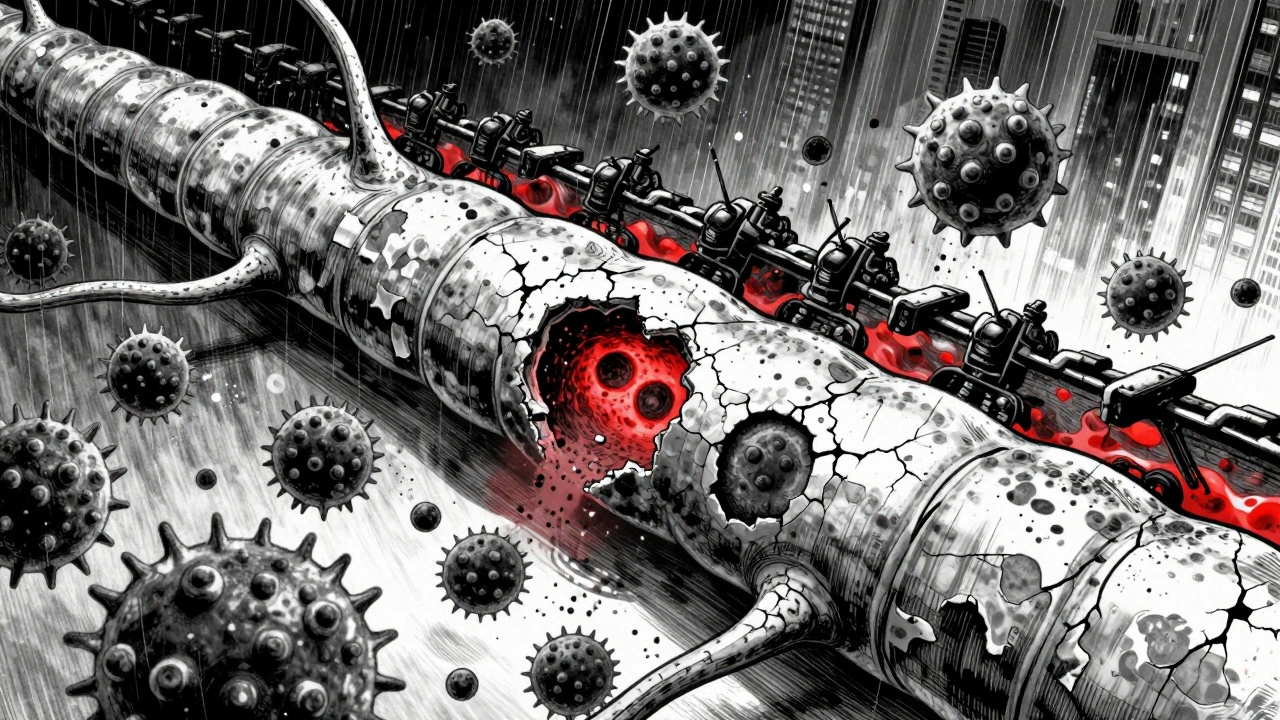

Your body has a built-in security system: immune cells that patrol for viruses, bacteria, and other invaders. In multiple sclerosis, something goes wrong. These cells-mainly T cells and B cells-mistake parts of your own nervous system for foreign threats. They cross the blood-brain barrier, a normally tight seal that keeps harmful substances out of the brain and spinal cord. Once inside, they start attacking myelin, the fatty substance that wraps around nerve fibers like insulation on an electrical wire.Without myelin, nerve signals become sluggish or blocked. Imagine trying to stream a video with a weak connection-sometimes it buffers, sometimes it cuts out. That’s what happens in your nervous system. The damage doesn’t stop there. Over time, the exposed nerve fibers (axons) begin to degrade. This is why MS isn’t just about flare-ups-it’s a progressive disease that can lead to permanent disability if unchecked.

Scientists have identified four distinct patterns of damage in MS tissue, each showing different combinations of immune cells, myelin loss, and nerve damage. But the common thread? Inflammation. Whether it’s T cells releasing toxic chemicals, B cells producing antibodies that attack myelin, or microglia (the brain’s own immune cells) going into overdrive, the result is the same: destruction of the nervous system’s wiring.

Why Does This Happen? The Triggers Behind the Attack

No one gets MS because of bad luck alone. It’s a mix of genes and environment. You’re more likely to develop it if you have a close relative with the disease, but even then, most people with those genes never get MS. Something else has to trigger it.One of the strongest links is the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), the virus that causes mononucleosis. Studies show people infected with EBV are 32 times more likely to develop MS than those who aren’t. It’s not that EBV causes MS directly-it’s more like it rewires your immune system in a way that makes it prone to attacking nerves.

Vitamin D deficiency is another major player. People living farther from the equator, where sunlight is weaker, have higher MS rates. Low vitamin D levels are linked to a 60% higher risk of developing the disease. Smoking also raises your risk by 80% and speeds up disability progression. It’s not just about avoiding these factors-it’s about understanding that your body’s defense system is being trained, over years, to turn on itself.

Women are two to three times more likely to get MS than men, especially in high-prevalence areas like Canada and Scandinavia. Why? Hormones, immune system differences, and possibly how women’s immune cells respond to environmental triggers may all play a role. The exact reason remains unclear, but the pattern is undeniable.

What Does an MS Attack Feel Like?

Symptoms vary wildly because MS can strike anywhere in the central nervous system. One person might lose vision in one eye. Another might struggle to feel their toes. Someone else might feel like they’re walking through deep water.The most common symptoms? Fatigue. Eight out of ten people with MS say it’s their biggest challenge-not just tiredness, but a crushing exhaustion that doesn’t go away with sleep. Numbness or tingling in limbs affects nearly 60% of patients. Vision problems, often from optic neuritis (inflammation of the optic nerve), can make colors fade or cause sudden, painful blurring. Walking becomes harder for more than 40% of people as muscle control weakens.

Then there’s Lhermitte’s sign: a sharp electric shock that runs down your spine when you bend your neck. It’s not dangerous, but it’s startling-and it’s a direct result of demyelination in the cervical spine. These aren’t random quirks. They’re the physical signatures of nerve damage.

Most people (about 85%) start with relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS). They have flare-ups-weeks or months of worsening symptoms-then periods where things get better, sometimes even back to normal. But each flare leaves behind some damage. Over time, the recovery gets less complete. About 15% of people have primary progressive MS (PPMS) from the start, with symptoms slowly getting worse without clear relapses.

How Doctors Are Fighting Back

There’s no cure yet, but treatments have improved dramatically in the last 20 years. The goal isn’t just to manage symptoms-it’s to stop the immune system from attacking.Disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) are the backbone of treatment. Ocrelizumab, for example, targets B cells. In clinical trials, it cut relapse rates by 46% in RRMS and slowed disability progression by 24% in PPMS. Natalizumab blocks immune cells from crossing the blood-brain barrier. It’s powerful-reducing relapses by 68%-but carries a small but serious risk of a rare brain infection called PML.

These drugs don’t fix existing damage. They prevent new attacks. That’s why early treatment matters. The sooner you start, the less cumulative damage you accumulate.

Researchers are now looking beyond suppression. Can we repair the damage? One promising drug, clemastine fumarate, showed in early trials that it could improve nerve signal speed by 35%-a sign that myelin might be regrowing. Other studies are exploring stem cells, immune reset therapies, and drugs that boost the brain’s own repair cells.

The New Frontiers: Biomarkers and Personalized Care

MS isn’t one disease. It’s a group of diseases with similar symptoms but different underlying causes. That’s why doctors are turning to biomarkers-measurable signs in the body that tell them what’s happening inside.One of the most promising is serum neurofilament light chain (sNfL). When nerves are damaged, this protein leaks into the spinal fluid and blood. Levels above 15 pg/mL indicate active inflammation with 89% accuracy. It’s becoming a key tool to decide whether a treatment is working-or if you need to switch.

Another discovery? Neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs). These are sticky webs of DNA and proteins released by immune cells that help trap germs-but in MS, they tear up the blood-brain barrier and wake up microglia. In 78% of acute MS relapses, NETs are elevated. Targeting them could open new treatment paths.

Researchers are also finding specific dendritic cells in the brain that act like traitors-presenting myelin to T cells and telling them, “Attack this.” Blocking these cells could stop the cycle before it starts.

What’s Next for People Living with MS?

The future isn’t just about better drugs. It’s about earlier detection, smarter monitoring, and repairing what’s already broken.People with MS are living longer, healthier lives than ever before. In the 1990s, half of untreated RRMS patients needed help walking within 15 to 20 years. Today, with modern treatments, that number has dropped to about 30%. That’s not just a statistic-it’s a life changed.

Research is now focused on stopping progression before it starts. Clinical trials are testing combinations of drugs that both calm the immune system and trigger myelin repair. The International Progressive MS Alliance has invested over $65 million into this work, funding projects across 14 countries.

For now, the message is clear: MS is not a death sentence. It’s a chronic condition that requires ongoing management. But with the right treatment, lifestyle choices, and support, many people live full, active lives-working, raising families, traveling, and even competing in sports.

The immune system may have turned against you. But science is learning how to turn it back.

Is multiple sclerosis hereditary?

MS isn’t directly inherited like eye color, but having a close relative with MS increases your risk. If a parent or sibling has it, your chance of developing MS is about 2-5%, compared to 0.1% in the general population. Genes play a role, but they’re only part of the story-environmental triggers like Epstein-Barr virus and low vitamin D are needed to set off the disease.

Can lifestyle changes help with MS?

Yes. Quitting smoking can slow disability progression by 80%. Getting enough vitamin D (through sun exposure or supplements) is linked to lower relapse rates. Regular exercise improves strength, balance, and fatigue. A healthy diet doesn’t cure MS, but it supports overall immune and nerve health. Stress management and good sleep also help reduce flare-ups.

Why do women get MS more often than men?

Women are 2 to 3 times more likely to develop MS, especially in high-prevalence regions. The exact reason isn’t known, but hormones-particularly estrogen and progesterone-likely influence immune activity. Women’s immune systems tend to be more reactive, which helps fight infections but may also increase the risk of autoimmune attacks. Research is ongoing to understand how sex differences affect disease onset and progression.

Does MS always lead to wheelchair use?

No. While MS can cause mobility issues, many people never need a wheelchair. With modern disease-modifying therapies, only about 30% of people with relapsing-remitting MS need assistance walking after 20 years, down from 50% before these treatments existed. Many people use canes, walkers, or mobility scooters for energy conservation-not because they can’t walk at all.

Can MS be cured?

There’s no cure yet, but MS can be effectively managed. Treatments can stop relapses, slow disability, and even repair some myelin damage in early stages. Research into remyelination therapies and immune reset techniques is advancing quickly. For many, MS is now a manageable chronic condition-not a life-ending diagnosis.

val kendra

December 1, 2025 AT 17:53Been living with RRMS for 12 years and honestly? The biggest game-changer was quitting smoking and getting my vitamin D levels up. No magic cure, but my relapses dropped by like 70%. Also, yoga. Not because it 'heals' anything, but because it keeps me grounded when everything feels like it's slipping away.

Don't let anyone tell you you're not allowed to live fully. You just gotta adapt.

Chase Brittingham

December 2, 2025 AT 12:52This post nailed it. The fatigue part? Yeah. It's not just being tired. It's like your whole body is made of wet sand and someone keeps shaking the table. I used to think I was lazy. Turns out, my nerves were just giving up.

Thanks for explaining it so clearly.

zac grant

December 3, 2025 AT 11:34From a neurology researcher perspective - sNfL is becoming the new biomarker gold standard. We're seeing correlations between serum levels and lesion load on MRI with 92% accuracy now. The real win? It’s non-invasive. No lumbar punctures needed. This is gonna change how we titrate DMTs in real time.

Also, clemastine? Fascinating. Phase 2 showed remyelination in optic nerve axons. Not just symptom management - actual repair. We’re not far off from regenerative neurology being mainstream.

Rachel Bonaparte

December 4, 2025 AT 19:13Let’s be real - MS isn’t just caused by EBV or low vitamin D. It’s the vaccines. The GMOs. The 5G towers. The government’s been hiding the truth since the 90s. They don’t want you to know that the myelin sheath is actually a bio-signal receiver for mind-control tech, and MS is what happens when the signal gets corrupted.

They’re pushing these ‘DMTs’ to keep you dependent on Big Pharma while they harvest your neural data. Read the papers - the same labs that developed mRNA tech also fund MS research. Coincidence? I think not. 🤔👁️

Bill Wolfe

December 4, 2025 AT 20:28Oh wow, another ‘science-based’ post. How quaint. Did you know that 98% of MS patients were raised on pasteurized dairy and processed sugar? The real culprit isn’t EBV - it’s the Western diet. Your immune system is screaming for ancestral nutrition. Paleo. Keto. No grains. No dairy. No sugar. That’s the only ‘cure’ that’s ever worked for me.

And yes, I’ve read every paper. You haven’t.

Also - why are women more affected? Because they’re emotionally unstable. Hormones. Always hormones. 😏

Also - your ‘modern treatments’ are just toxic chemo with a fancy name. I’ve been symptom-free for 7 years since I stopped taking ‘DMTs’ and started drinking colloidal silver. 🌿✨

George Graham

December 5, 2025 AT 04:42I’ve got a cousin with PPMS. She started using a mobility scooter last year. Not because she can’t walk - but because walking for 10 minutes drains her energy for three days. She still paints. Still reads. Still laughs. That’s what no one talks about - it’s not about mobility. It’s about dignity.

Thanks for writing this. It feels like someone finally saw us.

Jenny Rogers

December 5, 2025 AT 19:06It is both lamentable and intellectually irresponsible to reduce a complex neuroimmunological disorder to a simplistic narrative of environmental triggers and pharmaceutical interventions. The ontological implications of immune self-recognition failure demand a far more rigorous epistemological framework than the one presented here. One must interrogate not only the mechanistic pathways but also the sociohistorical construction of disease categorization in late-capitalist biomedicine.

Furthermore, the conflation of correlation with causation regarding EBV is a classic logical fallacy. One might as well blame the moon for tidal waves.

Until we deconstruct the hegemony of reductionist neurology, we remain complicit in the medicalization of human vulnerability.

Benjamin Sedler

December 6, 2025 AT 13:37So you’re telling me the immune system is the villain? Nah. The real villain is the fact that we still call it ‘multiple sclerosis’ instead of ‘the body’s way of saying ‘enough with the processed food and existential dread.’

Also, why is everyone obsessed with B cells? What about the gut? Have you heard of the gut-brain axis? No? Of course not. You’re all too busy chasing biomarkers while your microbiome is screaming in the dark.

Also - I’m pretty sure my cat cured my MS by staring at me intensely for 17 minutes every morning. Science hasn’t caught up yet. 😼

Libby Rees

December 7, 2025 AT 21:44My mother was diagnosed in 1987. She never took a DMT. She walked with a cane for 20 years. She taught high school biology. She never missed a day of work. She didn’t need to be ‘fixed.’ She needed to be understood.

There’s value in living with the condition, not just fighting it.

John Filby

December 9, 2025 AT 16:07Just had my first MRI since starting ocrelizumab. No new lesions. My sNfL dropped from 28 to 12. I cried in the parking lot.

Not because I’m cured. But because for the first time, I feel like I’m not losing ground.

Thank you for writing this. It’s the first time I’ve seen my experience reflected without pity or propaganda.

Still tired. Still numb sometimes. But not alone anymore. 🙏